All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Urtica dioica-Loaded Alginate Hydrogels for Antibacterial Oral Applications: Formulation and In Vitro Evaluation

Abstract

Introduction

The increasing resistance of oral pathogens to conventional antibiotics has stimulated the search for alternative, plant-derived antimicrobial agents. Urtica dioica (nettle) is a medicinal plant widely recognized for its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities. This study aimed to synthesize a hydrogel loaded with Urtica dioica extract and evaluate its antibacterial activity against two significant oral pathogens: Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli.

Materials and Methods

Ethanol extracts of nettle were incorporated into alginate hydrogels using a freeze-thaw synthesis technique. Characterization was carried out using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The antibacterial properties were assessed via the disc diffusion method.

Results

The hydrogels containing nettle extract demonstrated significant antibacterial activity against both tested strains. Zones of inhibition were significantly larger compared to blank hydrogels (p < 0.001). FTIR confirmed successful integration of active compounds, while SEM revealed a porous microstructure suitable for controlled release.

Discussion

Herbal oral formulations, such as those containing Urtica dioica, offer sustainable alternatives for controlling oral pathogens. Postbiotics have also emerged as novel anti-caries agents, and combining them with herbal bioactives has the potential to enhance antimicrobial efficacy.

Conclusion

Nettle extract-loaded hydrogels appear to be promising candidates for novel oral formulations for oral health applications, including mouthwashes and dental gels aimed at preventing or treating infections.

1. INTRODUCTION

Oral infectious diseases such as dental caries, gingivitis, and periodontitis are among the most prevalent health problems globally, with bacterial biofilms acting as primary etiological agents. Among the many microorganisms associated with oral infections, Streptococcus mutans, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli are frequently isolated from dental plaque, periodontal pockets, and infected oral wounds. These pathogens contribute to inflammation, tissue degradation, and tooth loss when not adequately controlled [1, 2].

Antibiotics have traditionally been used as the main line of defence against oral bacterial infections. However, the overuse and misuse of these drugs have led to alarming levels of antibiotic resistance, thereby reducing the effectiveness of conventional treatments [3]. This growing challenge has sparked renewed interest in the development of alternative antimicrobial strategies, especially those derived from natural and herbal sources.

In recent years, several herbal products have been investigated for their potential in promoting oral health and preventing common dental diseases. Extracts from green tea, clove, neem, miswak, and chamomile have shown strong antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects, reducing dental plaque, gingivitis, and caries incidence. For example, green tea catechins inhibit Streptococcus mutans adhesion, while neem and clove oils demonstrate broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Such herbal formulations are increasingly being incorporated into toothpastes and mouthrinses to support oral hygiene and periodontal health [4-7], and their incorporation into modern drug delivery platforms such as hydrogels represents a promising area of ongoing research.

Herbal medicine has been used across cultures for centuries to manage infectious diseases. Among these botanicals, Urtica dioica (commonly known as nettle) has attracted attention for its diverse pharmacological activities. The leaves and roots of nettle are rich in flavonoids, tannins, terpenoids, sterols, and phenolic compounds, many of which exhibit antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and wound-healing effects [8,9]. Several studies have shown that nettle extracts can inhibit the growth of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including oral pathogens [10-12].

In parallel, hydrogels, three-dimensional hydrophilic polymer networks, have gained popularity as advanced drug delivery systems. Their soft, mucoadhesive nature, along with the ability to encapsulate and sustain the release of active agents, makes them particularly suitable for intraoral applications [13]. Alginate-based hydrogels, derived from brown seaweed, are biodegradable, biocompatible, and widely used in biomedical applications [14].

The integration of nettle extract into a hydrogel matrix offers a novel approach to developing localized antimicrobial therapies that could circumvent systemic side effects and target pathogens directly at the site of infection. The objective of this study was to synthesize and characterize a nettle-extract-loaded hydrogel and evaluate its antibacterial efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli as representative oral pathogens.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Plant Material and Extraction

Dried Urtica dioica (nettle) leaves were obtained from a certified herbal supplier in Tabriz, Iran. The extraction method was adapted from previously published protocols with slight modifications [15, 16]. The plant material was ground to a fine powder using an electric grinder. For extraction, 50 grams of powdered leaves were soaked in 500 mL of 70% ethanol and macerated at room temperature for 24 hours with intermittent shaking. The resulting extract was filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper, concentrated using a rotary evaporator (Heidolph, Germany) under reduced pressure at 40°C, and stored at 4°C in dark containers until use. The Urtica dioica plant used in this study is not an endangered species and was handled according to institutional biosafety guidelines.

2.2. Hydrogel Preparation

A 13% (w/w) sodium alginate solution was prepared in distilled water under continuous stirring at room temperature. Nettle extract was then incorporated into the solution at a final concentration of 5% (w/w). The final concentration was selected based on preliminary tests evaluating viscosity, homogeneity, and antibacterial performance. This concentration provided optimal stability and diffusion characteristics within the hydrogel matrix, consistent with previous reports using similar plant-based formulations [14, 17]. The mixture was subjected to four freeze-thaw cycles (−20°C for 24 hours followed by thawing at 25°C) to form physically cross-linked hydrogels. This method was adapted from the hydrogel synthesis technique previously described by Thoniyot et al. (2015), which utilizes thermal cycling for non-toxic gelation and mechanical stability [15].

Blank hydrogels (without extract) were prepared using the same procedure to serve as controls.

2.3. Characterization of Hydrogels

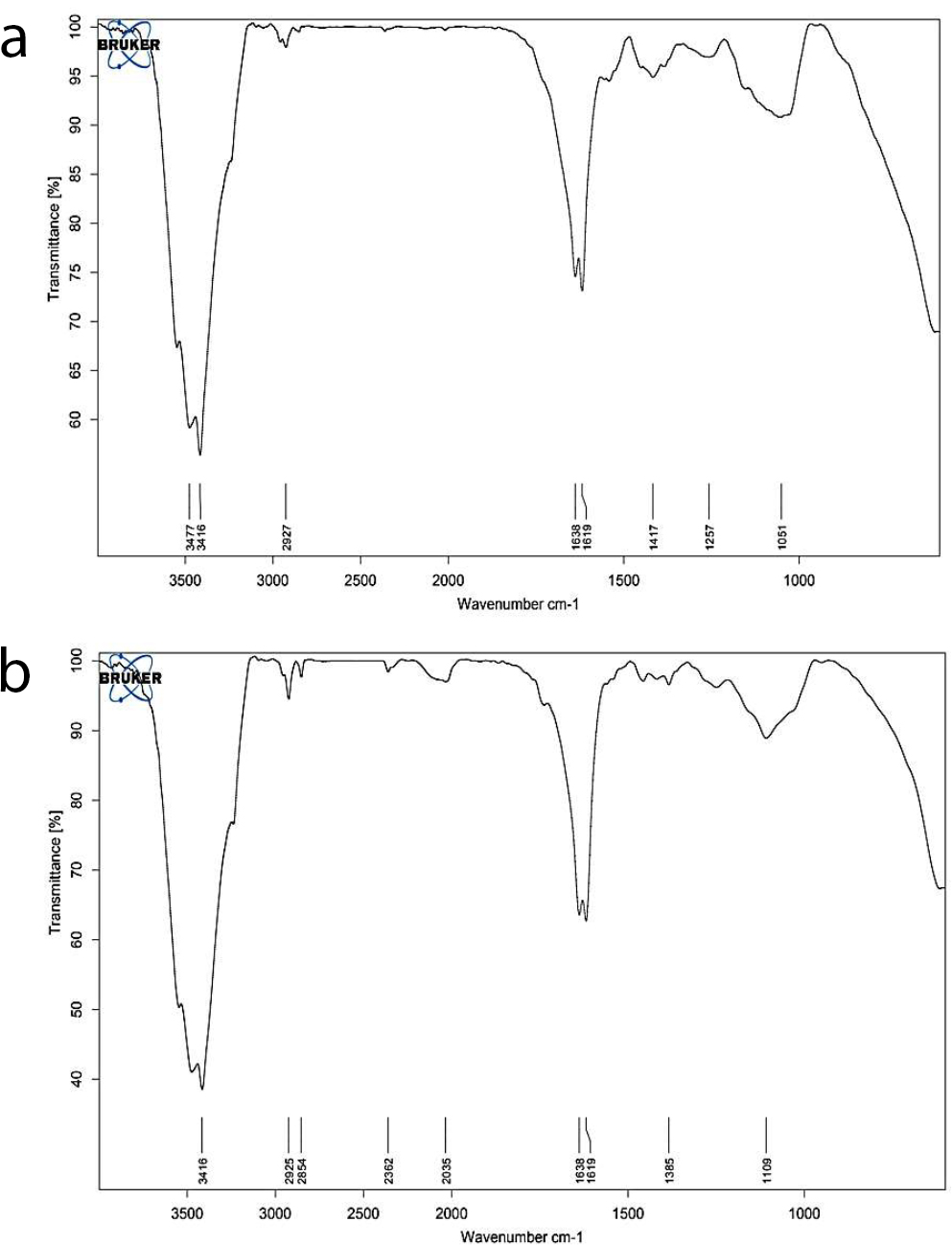

2.3.1. FTIR Analysis

The chemical interactions between Urtica dioica extract and the alginate matrix were investigated using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (Bruker Tensor 27, Germany) in the range of 400–4000 cm−1. This technique has been widely applied to identify hydrogen bonding and structural integration of bioactive compounds in hydrogel matrices [18].

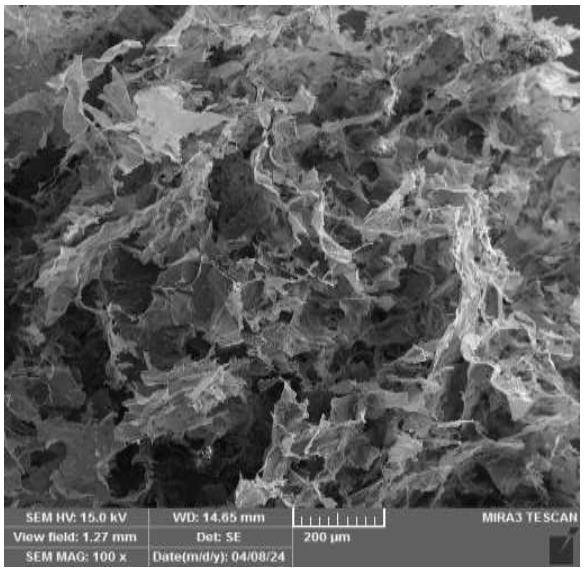

2.3.2. SEM Imaging

To assess the microstructure and porosity of the hydrogels, after lyophilization, samples were sputter-coated with gold and imaged using a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi SU3500, Japan). This approach provides critical insight into the internal morphology and is widely used in biomaterials research to evaluate diffusion potential and pore interconnectivity [19].

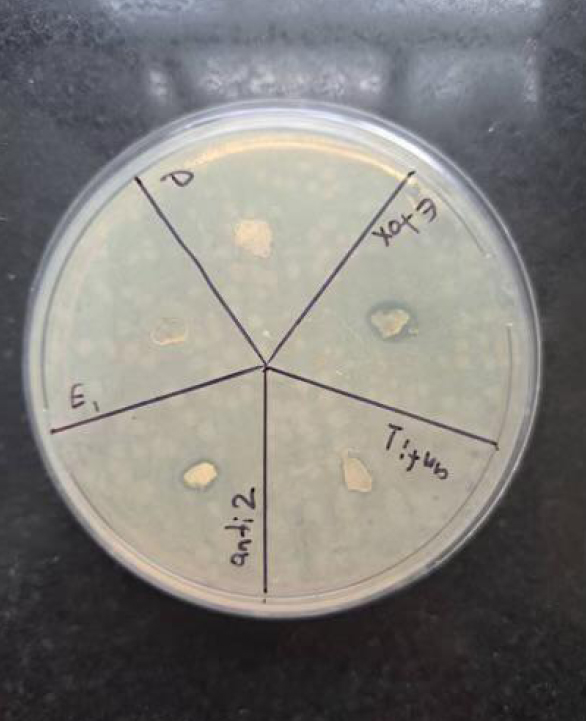

2.4. Antibacterial Assay

All bacterial strains used in this study were obtained from the Department of Microbiology, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, and handled according to institutional biosafety guidelines. The antibacterial activity of the hydrogels was assessed using the agar disc diffusion method against two oral pathogens: Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922). Mueller-Hinton agar plates were inoculated with standardized bacterial suspensions (0.5 McFarland standard). Hydrogel discs (6 mm diameter) were cut using a sterile punch and placed on the inoculated plates. Gentamicin (10 μg/disc) was used as the positive control, and blank hydrogels served as the negative control. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Zones of inhibition (in mm) were measured using a digital caliper.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. FTIR Analysis

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to analyze the chemical interactions between the alginate matrix and Urtica dioica extract. As shown in Figure 1a and b, the FTIR spectrum of pure sodium alginate exhibited characteristic absorption bands at 3233, 3211, 1410, 1131, 1111, and 1213 cm−1, corresponding to stretching vibrations of hydroxyl (–OH), carboxyl (COO−), and carbonyl (C=O) functional groups. In comparison, the FTIR spectrum of nettle-loaded alginate hydrogel displayed intensified peaks in the region of 3555–3155 cm−1 and 1355–1305 cm−1, which can be attributed to increased hydrogen bonding and the presence of carboxylic groups introduced by the plant extract. The new absorption bands around 1131 and 1111 cm−1 indicate the possible involvement of C=O and C=C groups, confirming the successful incorporation of phytochemical compounds into the hydrogel network.

3.2. SEM Imaging

The surface morphology of the hydrogels was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to evaluate internal structure and porosity. SEM images demonstrated a highly porous and sponge-like architecture in the nettle-loaded hydrogel sample, with numerous interconnected voids distributed throughout the matrix. This structure facilitates enhanced swelling and diffusion of bioactive compounds, which is essential for sustained antimicrobial activity and intraoral delivery (Fig. 2).

3.3. Antibacterial Activity

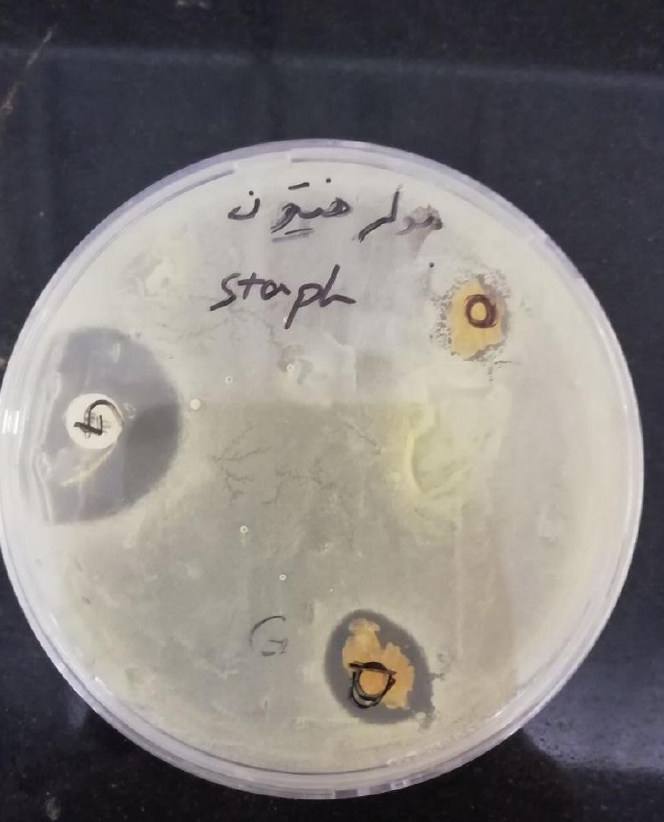

The antimicrobial efficacy of the nettle-loaded hydrogels was assessed using the disc diffusion method against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Nettle-loaded hydrogels produced significantly larger inhibition zones compared to blank hydrogels (p < 0.001), which showed no antibacterial effect. Specifically, the mean inhibition zone for Staphylococcus aureus was 16.1 ± 1.2 mm, and for Escherichia coli, 14.3 ± 1.3 mm. Gentamicin served as a positive control with inhibition zones of 23.4 ± 1.6 mm and 8.7 ± 1.1 mm for Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, respectively (Table 1). As shown in Figures 3 and 4, Urtica dioica-loaded hydrogels produced clear inhibition zones against both E. coli and S. aureus, whereas blank hydrogels exhibited no antibacterial activity.

4. DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the antibacterial efficacy of Urtica dioica extract incorporated into alginate-based hydrogels against two common oral pathogens, Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Results showed that nettle-loaded hydrogels exhibited significantly larger zones of inhibition than blank hydrogels (p < 0.001), indicating their potential as bioactive delivery systems for oral antimicrobial applications.

The antimicrobial effect is attributed to various phytochemicals in Urtica dioica, including flavonoids (e.g., quercetin), phenolic acids (e.g., chlorogenic and caffeic acids), and tannins. These compounds are known to disrupt bacterial membranes, inhibit nucleic acid synthesis, and interfere with key enzymatic processes [20, 21]. Consistent with our findings, Mirtaghi et al. and Moradi et al. demonstrated that ethanolic and hydroalcoholic nettle extracts possess significant bacteriostatic activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli [10, 16].

The greater inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus could be explained by the structural differences in the cell walls of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Gram-positive bacteria have a thicker peptidoglycan layer that is more accessible to hydrophilic and polyphenolic compounds, whereas the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria can limit the penetration of many bioactive agents [22, 23].

FTIR analysis confirmed chemical interactions, especially hydrogen bonding, between nettle extract and the alginate matrix, suggesting successful incorporation of bioactive compounds [24]. SEM images showed a highly porous, interconnected microstructure, facilitating hydrogel swelling, active compound retention, and controlled release—key characteristics for intraoral drug delivery [19, 25].

| Bacterial Strain | Nettle Hydrogel | Blank Hydrogel | Gentamicin (10 μg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 16.1± 1.2 (14.3 – 17.9) | 0 ± 0 (0 – 0) | 23.4 ± 1.6 (21.0 – 25.8) |

| Escherichia coli | 14.3± 1.3 (12.3 – 16.3) | 0 ± 0 (0 – 0) | 8.7 ± 1.1 (7.0 – 10.4) |

FTIR spectra of (a) pure sodium alginate and (b) nettle-loaded alginate hydrogel, showing shifts and intensification of peaks in the hydroxyl and carboxyl regions, indicative of successful hydrogel formation and phytochemical integration.

SEM micrograph of nettle-loaded alginate hydrogel (magnification: 100×), showing a highly porous microstructure with abundant cavities and interconnected channels. (SEM HV: 15.0 kV, WD: 14.65 mm, scale bar: 200 µm, device: MIRA3 TESCAN, Date: 24/08/04).

Antibacterial activity of different Urtica dioica-loaded alginate hydrogel formulations against Escherichia coli on Mueller–Hinton agar. Distinct inhibition zones are observed around extract-loaded hydrogels, while blank hydrogels show no inhibition. Each labeled section represents a different test formulation.

Antibacterial activity of Urtica dioica-loaded alginate hydrogels against Staphylococcus aureus on Mueller–Hinton agar. Clear inhibition zones are visible around the extract-loaded hydrogels, whereas blank samples exhibited no antibacterial effect. Gentamicin discs served as positive controls.

Alginate was selected as the hydrogel base due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mucoadhesive properties, making it ideal for oral applications [26, 27]. Previous studies have demonstrated that alginate-based hydrogels support localized delivery of therapeutic agents while maintaining a favorable biological profile [14, 27]. Therefore, combining Urtica dioica extract with alginate offers a synergistic platform for creating natural, localized antibacterial therapies.

In this study, blank sodium alginate hydrogels showed no antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus or Escherichia coli, with inhibition zones measuring 0.0 mm. This observation is consistent with numerous studies reporting that unmodified alginate hydrogels generally lack intrinsic antimicrobial properties. Several reviews and experimental investigations indicate that alginate alone does not inhibit bacterial growth unless combined with antimicrobial agents, such as metal nanoparticles, plant extracts, or antibiotics [28, 29]. For instance, the antimicrobial activity observed in alginate-based materials is commonly attributed to the incorporated bioactive substances rather than to the alginate polymer matrix. Therefore, the absence of antibacterial activity in the blank hydrogels in our study supports the conclusion that the observed antibacterial activity is due to the Urtica dioica extract incorporated into the hydrogel, rather than to the polymeric matrix itself.

Recently, postbiotics have attracted attention as novel agents for the prevention of dental caries. They target cariogenic bacteria and modulate the oral microbiome. They exert multifunctional biological effects, including inhibition of cariogenic bacteria such as Streptococcus mutans, modulation of oral biofilm composition, and enhancement of mucosal immune responses, without the safety concerns associated with live probiotic administration [6, 30]. Postbiotics achieve these effects primarily by producing organic acids, bacteriocins, and other antimicrobial peptides, as well as by regulating host immune pathways and oxidative balance [31].

Although Urtica dioica is not a postbiotic, its high levels of flavonoids and phenolic compounds suggest potential synergy when incorporated into postbiotic-based delivery systems. The bioactive phytochemicals of Urtica dioica possess antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties that could complement postbiotic mechanisms by disrupting bacterial membranes, inhibiting biofilm formation, and reducing oxidative stress. Such hybrid Urtica dioica–postbiotic hydrogels have the potential to enhance oral microbiome balance, prevent caries formation, and promote gingival health [32, 33]. However, this innovative concept remains largely unexplored and warrants further in vitro and in vivo investigations to validate the potential synergistic effects between plant-derived bioactives and postbiotic metabolites.

5. LIMITATIONS

Despite promising outcomes, this study has several noteworthy limitations. The findings are based solely on in vitro assays, which, although informative, cannot fully replicate the complex in vivo environment of the oral cavity, where factors such as saliva flow, enzymatic activity, immune responses, and microbiome interactions may influence the hydrogel’s stability and antibacterial performance. The antibacterial assessment was limited to two bacterial species, and anaerobic periodontal pathogens such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia were not evaluated, thereby limiting its applicability to the complex oral microbiome. Additionally, cytotoxicity and biocompatibility on human oral epithelial and gingival cells were not investigated, which are essential for assessing clinical safety. Future studies should include biofilm-based models, evaluation of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) against a broader range of oral microorganisms, cytotoxicity testing, long-term stability assessments, and in vivo animal models to confirm the safety, efficacy, and clinical applicability of Urtica dioica-loaded hydrogels in oral healthcare.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated that Urtica dioica-loaded alginate hydrogels possess significant antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, highlighting their potential as natural, plant-based alternatives for localized oral antimicrobial therapy. The biodegradable and mucoadhesive properties of alginate make these hydrogels suitable for intraoral applications. Future studies are warranted to evaluate cytotoxicity and explore integration with postbiotic formulations to further enhance their clinical potential.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: P.M.: Conceptualized the study and supervised the research process; B.H.: was responsible for data collection, sample preparation, and execution of laboratory experiments; P.M.: Performed data analysis, prepared the figures and tables, and drafted the initial manuscript. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| FTIR | = Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| SEM | = Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| MIC | = Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MBC | = Minimum Bactericidal Concentration |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences with the ethical code IR.TBZMED.VCR.REC.1402.241 to comply with biosafety regulations for microbial research.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Microbiology Department of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for laboratory support.