All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Dental Implants and Idiopathic Osteosclerosis: Two Case Reports

Abstract

Background

Idiopathic osteosclerosis (IO) is a benign, localized bone lesion often discovered incidentally during radiographic examinations. While typically asymptomatic, its presence in potential dental implant sites may complicate treatment planning and osseointegration. This case report examines the clinical implications of IO in implant dentistry, focusing on diagnostic challenges, surgical considerations, and treatment outcomes.

Case Presentation

Two cases are presented: a successful implant placement in a maxillary IO lesion with favorable osseointegration, and a failed implant adjacent to an IO lesion that developed significant bone loss. Radiographic, surgical, and histological findings are discussed, highlighting the variability in treatment outcomes.

Conclusion

IO presents both opportunities and challenges in implant therapy. While dense sclerotic bone may enhance primary stability, its altered biological properties can affect long-term success. Careful case selection, modified surgical techniques, and thorough patient counseling are essential when encountering IO in implant dentistry. These cases underscore the need for further research to establish evidence-based management protocols.

1. INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic osteosclerosis (IO), also known as dense bone island or enostosis, is a benign condition characterized by localized, radiopaque bone lesions that lack a clear pathological cause [1, 2]. These lesions are frequently observed around the roots of teeth, particularly in the mandible, and are often detected incidentally during routine radiographic examinations, such as digital panoramic radiography or cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) [2, 3]. The prevalence of IO varies widely across populations, ranging from 2.3% to 31%, depending on diagnostic criteria, imaging techniques, and demographic factors [4]. Higher prevalence rates have been reported in Asian and African populations, while studies in Iranian and Brazilian cohorts report frequencies of 2.84% and 5.6%, respectively [4, 5]. IO exhibits no significant gender predilection, though some studies suggest a slight female predominance [2].

The etiology of IO remains uncertain, but several hypotheses have been proposed. Some researchers suggest that local mechanical factors, such as increased occlusal stress or chronic low-grade trauma, may contribute to its development. Others speculate that it could represent a developmental anomaly or a reactive bone response to previous inflammation. Unlike other sclerotic bone lesions (e.g., condensing osteitis or cemento-osseous dysplasia), IO is typically asymptomatic and does not require intervention unless complications arise [4-6].

Clinically, IO presents as a well-defined, non-expansile radiopacity, most commonly found in the mandible (90–95% of cases), particularly in the premolar and molar regions [5]. Lesions may appear round, ovoid, or irregular in shape and are often located near tooth roots, though they can also occur in edentulous areas [2, 5]. Unlike condensing osteitis or cemento-osseous dysplasia, IO is not associated with inflammation, caries, or pulpal pathology, and adjacent teeth typically remain vital [7]. While most cases are asymptomatic, rare complications include tooth displacement, root resorption, or interference with orthodontic treatment [8].

The prognosis for IO is generally excellent, as these lesions are considered developmental variations of normal bone architecture rather than pathological entities [2, 5]. Longitudinal studies indicate that IO remains stable in size and morphology over time, particularly in adults, with no malignant transformation reported [9]. In children and adolescents, lesions may exhibit slow growth but typically stabilize by skeletal maturity [7]. Management usually consists of radiographic monitoring, with intervention reserved only for cases causing clinical complications, such as impaired tooth eruption or prosthetic interference [7, 9].

Despite its benign nature, IO can present clinical challenges, particularly in dental implantology. The presence of sclerotic bone may interfere with implant placement, osseointegration, or prosthetic rehabilitation. Additionally, IO has been associated with external root resorption and, in rare cases, inferior alveolar neuralgia due to compression of adjacent structures. Accurate radiological differentiation from other pathologies (e.g., osteomas, odontomas, or metastatic bone lesions) is essential to avoid unnecessary biopsies or overtreatment [10-15].

Given the increasing use of dental implants in modern dentistry, understanding the implications of IO in bone density, healing response, and long-term implant success is crucial. This case report examines two instances where IO influenced implant therapy outcomes, highlighting the importance of preoperative assessment, histological confirmation, and tailored surgical approaches in such scenarios.

2. CASE PRESENTATION

The ethical approval for publication of this case report was provided by the ethical review board of Tishreen University Hospital with number 3121 on June 6, 2024.

2.1. Case 1

A 62-year-old female patient presented for maxillary rehabilitation with an implant-supported fixed prosthesis. Clinical examination revealed a failing conventional fixed partial denture extending from tooth #14 to #21, exhibiting significant gingival recession and radiographic evidence of periapical pathology. Preoperative cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) using a Planmeca ProMax 3D unit demonstrated a well-defined radiopaque lesion measuring 1.5 × 1.3 cm adjacent to tooth #16, with a buccal-palatal width of 8.2 mm and bone density measuring 1250 Hounsfield units (Fig. 1).

Preoperative OPG showing a radiopaque lesion on the right posterior maxilla.

A treatment plan was formulated for maxillary rehabilitation with a fixed implant-supported prosthesis. A right lateral implant was planned within the dense bone area, and a bone biopsy was performed to assess the lesion.

The surgical procedure was performed under local anesthesia using 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. A full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap was elevated, and implant site preparation was initiated with a 2.2 mm pilot drill from the MegaGen surgical kit under copious saline irrigation at 30 mL/min. Sequential osteotomy expansion was performed using the MegaGen drill sequence, progressing to 3.5 mm and 4.5 mm diameters, followed by final site preparation with a 5.0 mm countersink drill. A MegaGen AnyOne 4.5 × 11 mm implant with a sandblasted, large-grit, acid-etched (SLA) surface was placed with an insertion torque of 45 Ncm using the MegaGen torque controller.

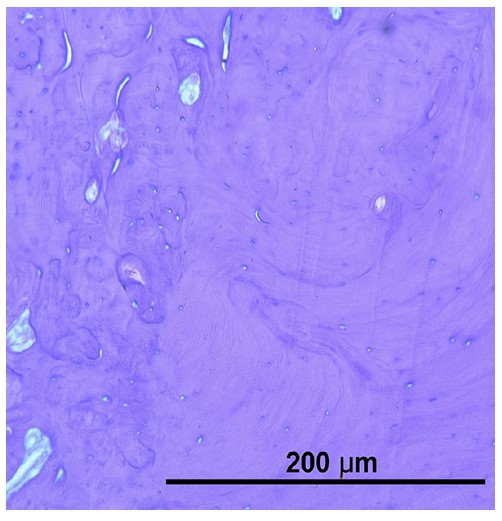

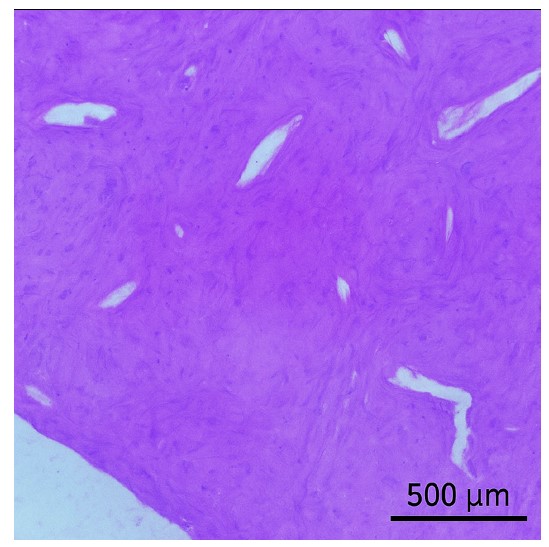

Histological examination revealed complete replacement of normal bone structure with a sclerotic osseous mass, including detectable Haversian systems. The diagnosis of idiopathic osteosclerosis was confirmed based on clinical, radiological, and histological findings (Fig. 2).

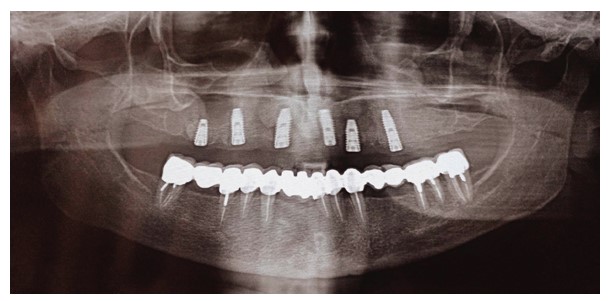

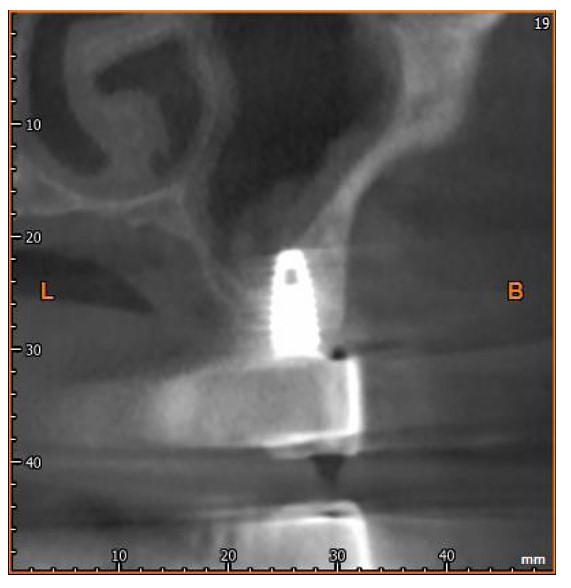

After six months, the implants were exposed, healing abutments were placed, and prosthetic procedures began (Figs. 3 and 4). The RFA of the implant within the lesion revealed a measurement of 83.

The prosthetic phase involved taking an open-tray impression, followed by fabrication of a CAD/CAM milled titanium abutment and a 12-unit zirconia-based fixed prosthesis, which was cemented with temporary cement.

Histological examination of the radiopaque lesion confirming the diagnosis of osteosclerosis.

OPG 6 months after surgery showing the success of the dental implant placed within the osteosclerotic area.

CBCT scan 12 months after surgery.

2.2. Case 2

A female patient in her 50s sought rehabilitation for the posterior maxilla with a fixed implant-supported prosthesis. Clinical examination revealed missing maxillary premolars and molars, with residual roots in the maxillary first molar region. OPG and CBCT scans indicated sufficient bone for implant placement in the premolar region, and residual roots were noted in the molar region (Figs. 5 and 6).

Periapical view of the maxillary molar region showing unrestorable roots, as well as a radiopaque lesion on the periapical plane that was not noticed during the preoperative radiograph.

Two MegaGen ST implants (MegaGen Implant Company, South Korea) were placed. At the four-month follow-up, the maxillary first molar implant was exposed, with a significant periodontal pocket detected around it despite stability. OPG revealed bone resorption around the implant (Fig. 7), and CBCT identified a 0.5 mm radiopaque mass resembling residual roots. The implant was removed, the mass was excised, and the area was cleaned. Histological analysis confirmed osteosclerosis (Fig. 8).

Preoperative scan showing the location of the lesion noted when reviewing scans after implant failure.

OPG 6 months after surgery showing significant bone resorption around the dental implant.

Histological examination of the radiopaque lesion after removing the lesion and the dental implant.

3. DISCUSSION

Idiopathic osteosclerosis (IO) remains an enigmatic condition in dental practice, often discovered incidentally during radiographic examinations [16]. The cases presented here illustrate the clinical challenges associated with IO, particularly in the context of dental implant therapy. While traditionally considered a benign anatomical variant with little clinical significance, these cases demonstrate that IO may have substantial implications for treatment planning and outcomes in implant dentistry [17, 18]. The radiographic presentation of IO as a well-defined radiopacity without associated symptoms typically leads to its classification as a non-pathological finding [2, 13]. However, its presence in potential implant sites necessitates careful consideration due to the altered bone structure and potential impact on osseointegration [17, 19].

The first case demonstrated successful osseointegration despite the presence of IO, with favorable stability values observed during follow-up examinations. This outcome suggests that dense sclerotic bone may not necessarily contraindicate implant placement, provided appropriate surgical techniques are employed [20, 21]. The high insertion torque achieved during placement and subsequent increase in resonance frequency analysis values indicate that the mechanical properties of sclerotic bone can, in some cases, contribute to favorable primary stability [21, 22]. However, the biological behavior of such bone remains questionable, as the reduced vascularity typical of sclerotic lesions might theoretically compromise the healing response [23-25]. The histological findings in this case, showing replacement of normal bone architecture with dense lamellar bone containing Haversian systems, confirm the diagnosis while highlighting the structural differences from normal alveolar bone [22, 26].

In contrast, the second case resulted in implant failure, with significant bone loss observed around the implant placed in proximity to an IO lesion. This divergent outcome underscores the unpredictable nature of IO in clinical practice and suggests that the relationship between sclerotic bone and implant success may be more complex than simple mechanical considerations. The failure in this case may be attributed to several factors, including possible compromised blood supply in the sclerotic region, altered bone remodeling capacity, or excessive occlusal forces concentrated in the area of abnormal bone density. The finding that the lesion was initially mistaken for a residual root fragment further emphasizes the diagnostic challenges posed by IO and the importance of thorough radiographic evaluation prior to implant placement [26-28].

The variability in outcomes between these two cases mirrors the broader uncertainty in the literature regarding the clinical significance of IO. While some studies suggest that dense bone islands may actually enhance implant stability, others report complications similar to those observed in our second case. This discrepancy may be explained by differences in lesion size, location, and the specific characteristics of the surrounding bone. The mandibular prevalence of IO noted in epidemiological studies was not observed in our cases, both of which involved maxillary lesions, suggesting that the anatomical location may influence the clinical impact of these lesions [26-28].

From a surgical perspective, these cases highlight the need for modified techniques when operating on a sclerotic bone. The increased density requires careful drilling protocols to avoid excessive heat generation and subsequent bone necrosis. The use of graduated drill sizes with copious irrigation becomes particularly important in such cases. Additionally, the decision to perform a biopsy, as done in the first case, should be weighed against the potential risks, as the procedure itself may compromise the implant site. The diagnostic certainty provided by histological examination must be balanced against the additional surgical trauma introduced by the biopsy procedure [29-33].

Prosthetically, the presence of IO may influence loading protocols and long-term maintenance. While immediate loading might be tempting in cases demonstrating excellent primary stability, the biological uncertainties surrounding sclerotic bone suggest that a more conservative approach with delayed loading may be prudent [34]. Regular monitoring through clinical and radiographic examinations becomes particularly important for implants placed in or near areas of osteosclerosis, as the remodeling capacity of such bone may differ from normal alveolar bone. The development of peri-implant bone loss in the second case, despite initial stability, serves as a cautionary example of the potential for late-term complications [35-37].

The broader implications of these findings extend to treatment planning and patient consent processes. Patients should be informed about the potential for altered healing when implants are placed in areas of sclerotic bone, and alternative treatment options should be considered when IO lesions are particularly extensive or unfavorably located. The cases also raise questions about the need for routine radiographic screening for bone abnormalities prior to implant placement, as undetected IO lesions could potentially affect treatment outcomes.

While the current study has presented two cases of IO with divergent implant outcomes, several other case reports in the literature further illustrate the clinical spectrum of this condition. For instance, Chen documented a successful implant placement in a mandibular IO lesion, achieving osseointegration despite the sclerotic bone's reduced vascularity, corroborating our first case's findings [17]. Conversely, Taghsimi et al. [20] reviewed hyperdense jaw lesions and noted implant failures in 15.8% of cases involving IO, aligning with our second case's outcome. These reports underscore the unpredictable nature of IO, where dense bone may enhance primary stability but compromise long-term success due to altered remodeling capacity [20, 38].

The literature reveals a dichotomy: some studies advocate for IO's mechanical advantages in implant stability [17, 19], while others caution against its biological limitations [23, 25]. For example, Seo et al. demonstrated that under-drilling and osseodensification techniques improved outcomes in low-density bone, which could be adapted for sclerotic lesions [13]. Conversely, Kohli et al. identified micromotion thresholds as critical for osseointegration, suggesting that IO's rigidity might exceed optimal levels [19].

Based on the findings of these cases and existing literature, a stepwise approach is recommended for managing IO in implant dentistry. First, a thorough preoperative assessment using advanced imaging (e.g., CBCT) is essential to evaluate the size, location, and density of the lesion. For lesions in critical implant sites, a biopsy may be warranted to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other pathologies. During surgery, modified drilling protocols, such as gradual osteotomy preparation with copious irrigation, should be employed to minimize thermal injury to the sclerotic bone. High insertion torque should be achieved cautiously, balancing primary stability with the risk of microfractures. Postoperatively, a delayed loading protocol is advisable to allow for adequate biological adaptation, and close monitoring via clinical and radiographic follow-ups is critical to detect early signs of failure. Patient counseling about the potential risks and benefits of implant placement in IO-affected bone is also paramount.

The first case demonstrated successful osseointegration despite the presence of IO, with favorable stability values observed during follow-up examinations. This outcome suggests that dense sclerotic bone may not necessarily contraindicate implant placement, provided appropriate surgical techniques are employed [20, 21]. The high insertion torque achieved during placement and subsequent increase in resonance frequency analysis values indicate that the mechanical properties of sclerotic bone can, in some cases, contribute to favorable primary stability [21, 22]. However, the biological behavior of such bone remains questionable, as the reduced vascularity typical of sclerotic lesions might theoretically compromise the healing response [22, 26, 27]. The histological findings in this case, showing replacement of normal bone architecture with dense lamellar bone containing Haversian systems, confirm the diagnosis while highlighting the structural differences from normal alveolar bone [22, 26].

The biological behavior of idiopathic osteosclerosis (IO) and its implications for dental implant success may be influenced by systemic hormonal regulation of bone metabolism. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) and vitamin D play critical roles in calcium-phosphate homeostasis, with PTH promoting bone resorption to maintain serum calcium levels, while vitamin D enhances intestinal calcium absorption and bone mineralization [39, 40]. In IO lesions, the dense sclerotic bone exhibits reduced vascularity and osteoblastic activity, as evidenced by immunohistochemical staining showing minimal osteocalcin (OCN) expression, a marker of osteoblast function [17]. This suggests that IO may disrupt local bone remodeling dynamics, potentially impairing the osseointegration process, particularly in cases where altered PTH or vitamin D levels further compromise bone turnover [40, 41]. Additionally, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) imbalances, as seen in hypo- or hyperthyroidism, can exacerbate bone density abnormalities, with hypothyroidism linked to delayed healing and hyperthyroidism to excessive resorption, both of which may destabilize implants placed in IO-affected sites [39-41].

Sex hormones, particularly estrogen, also modulate bone metabolism by inhibiting osteoclast activity and promoting osteoblast survival. Postmenopausal estrogen deficiency is associated with accelerated bone loss and reduced trabecular connectivity, which may contrast with the hypermineralized but biologically inert nature of IO [40, 41]. Studies indicate that estrogen deficiency can elevate pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, RANKL), further skewing bone turnover toward resorption, a process that may exacerbate peri-implant bone loss when combined with IO’s inherent remodeling deficits [40, 41]. Conversely, the dense lamellar structure of IO might initially enhance primary implant stability due to high mechanical resistance, but its poor capacity for adaptive remodeling could hinder long-term osseointegration, especially under occlusal loading [17, 20]. These findings underscore the need for preoperative hormonal assessments and tailored surgical protocols (e.g., modified drilling techniques, delayed loading) to mitigate risks in IO patients [20, 42].

The implant failure observed in case 2 may indeed be linked to peri-implantitis, a biofilm-associated inflammatory condition characterized by progressive bone loss around implants [42, 43]. Peri-implantitis shares pathogenic mechanisms with periodontitis but exhibits more aggressive bone resorption due to the absence of periodontal ligament-mediated adaptive responses [44]. Bone metabolism plays a critical role in peri-implantitis progression, as elevated inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) disrupt the RANKL/OPG balance, promoting osteoclast activity and impairing osteoblast function [42, 45]. Systemic factors, such as diabetes, exacerbate this imbalance by increasing advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which further amplify oxidative stress and impair osseous healing [46]. Local risk indicators, including plaque accumulation and inadequate prosthetic design, create a permissive environment for dysbiotic biofilm formation, while patient-specific factors, like sex (e.g., postmenopausal estrogen deficiency) and diabetes mellitus, significantly elevate susceptibility to peri-implant bone loss [43, 44, 47]. These findings underscore the multifactorial nature of peri-implantitis, necessitating comprehensive risk assessment and tailored maintenance protocols to mitigate failure [46, 48].

This study has provided valuable insights into the clinical implications of idiopathic osteosclerosis (IO) in dental implantology through detailed case presentations, highlighting both successful and failed outcomes. The use of advanced diagnostic tools, such as CBCT and histological analysis, strengthens the reliability of the findings, while the inclusion of resonance frequency analysis (RFA) offers objective measures of implant stability. The discussion of modified surgical techniques and the emphasis on individualized treatment planning are practical strengths that can guide clinicians. However, the study is limited by its small sample size of only two cases, which restricts the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the short follow-up period (6–12 months) may not fully capture long-term outcomes or potential late complications. The lack of a control group or standardized protocol for comparison further limits the ability to draw definitive conclusions. Despite these limitations, the study underscores the need for further research with larger cohorts and longer follow-up periods to establish evidence-based guidelines for managing IO in implant dentistry.

Future research should focus on longitudinal studies of implant survival in IO-affected bone, as well as investigations into the cellular and molecular characteristics of these lesions. The development of standardized protocols for managing IO in implant dentistry could be valuable, particularly given the increasing prevalence of implant therapy in aging populations where incidental findings like IO become more common. Advanced imaging techniques, including three-dimensional analyses of bone density and vascularity, may provide further insights into the biological behavior of these lesions and their interaction with dental implants.

As implant dentistry continues to evolve, a deeper understanding of conditions like IO will become increasingly important for optimizing treatment outcomes and minimizing complications. The paradoxical nature of these lesions, providing mechanical advantage while potentially compromising biological response, serves as a reminder of the complex relationship between bone structure and implant success. This study has several limitations that warrant discussion. First, the small sample size (two cases) restricts the generalizability of the findings, and the absence of a control group limits comparative analysis. Second, the relatively short follow-up period (6–12 months) may not fully capture late-stage complications, such as peri-implant bone loss or prosthetic failures. Third, potential selection bias exists, as both cases involved maxillary IO lesions, whereas the mandible is the more common site for such lesions. Additionally, the retrospective design introduces inherent biases, including reliance on historical clinical records and imaging.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, while idiopathic osteosclerosis typically represents a benign radiographic finding, its presence in potential implant sites warrants careful consideration. The cases presented here demonstrate that IO can influence implant outcomes in both positive and negative ways, suggesting that an individualized approach to treatment planning is essential.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Z.A., A.K.: Study conception and design; Z.A., I.A.: Data collection; Z.A., A.K., W.K.: Analysis and interpretation of results; Z.A., I.A.: Drafting of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| IO | = Idiopathic osteosclerosis |

| CBCT | = Cone-beam computed tomography |

| SLA | = Sandblasted, large-grit, acid-etched |

| RFA | = Resonance frequency analysis |

| CAD/CAM | = Computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing |

| OPG | = Orthopantomogram (panoramic radiograph) |

| PTH | = Parathyroid hormone |

| OCN | = Osteocalcin |

| TSH | = Thyroid-stimulating hormone |

| IL-6 | = Interleukin-6 |

| RANKL | = Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand |

| TNF-α | = Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| OPG | = Osteoprotegerin |

| AGEs | = Advanced glycation end products |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tishreen University, Syria with Ethical approval no. 3121.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee, and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Z.A], on special request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.