All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Association between Salivary Vitamin D Levels and Periodontal Disease Severity: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

Introduction

Vitamin D supports periodontal health by modulating immunity and bone metabolism. As a non-invasive diagnostic fluid, saliva may reflect systemic vitamin D status and serve as a potential biomarker for periodontal health. This study aimed to compare salivary vitamin D levels between patients with periodontitis and healthy subjects, and to investigate their association with key clinical periodontal parameters.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted, including 100 participants (50 with periodontitis and 50 healthy controls). Unstimulated saliva samples were collected and analysed for vitamin D concentration using ELISA. Clinical periodontal parameters, including probing pocket depth (PPD), clinical attachment loss (CAL), and bleeding on probing (BOP), were recorded and analysed for correlations with salivary vitamin D levels.

Results

Salivary vitamin D levels were significantly lower in the periodontitis group compared to healthy controls (p < 0.01). Moreover, salivary vitamin D levels demonstrated a moderate negative correlation with PPD, CAL, and BOP.

Discussion

These findings suggest that reduced salivary vitamin D levels are associated with increased periodontal disease severity. However, due to the cross-sectional design, causal relationships cannot be established.

Conclusion

Lower salivary vitamin D levels are associated with periodontal disease severity, suggesting that salivary vitamin D may serve as a non-invasive biomarker for periodontal disease severity assessment. However, further longitudinal and interventional studies are warranted to confirm these findings.

1. INTRODUCTION

Periodontal diseases, particularly periodontitis, are chronic, prevalent inflammatory disorders characterized by progressive destruction of the supporting structures of the teeth, potentially leading to tooth loss if left untreated [1, 2]. The etiology of periodontitis is multifactorial, involving a complex interplay between pathogenic microbial biofilms and the host’s immune-inflammatory response [3]. Early identification of modifiable risk factors and reliable biomarkers is critical for the effective diagnosis, monitoring, and management of periodontal disease [4].

Vitamin D, a fat-soluble secosteroid hormone primarily responsible for calcium and phosphate homeostasis, is essential for maintaining bone mineralization and skeletal integrity [5, 6]. Vitamin D also plays a key role in regulating immune responses and inflammation [7, 8]. These effects are mediated via the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which is expressed on immune cells such as macrophages and T cells [9, 10].

Numerous epidemiological and clinical studies have reported an association between vitamin D deficiency and increased susceptibility to chronic inflammatory conditions, including periodontitis [11-15]. Lower serum vitamin D levels are correlated with greater clinical attachment loss (CAL), deeper probing pocket depth (PPD), and increased periodontal inflammation [16-18]. However, most studies have focused predominantly on serum vitamin D concentrations.

Saliva, as a diagnostic medium, offers a cost-effective and patient-friendly alternative for assessing both systemic and local biomarkers [19]. Due to its ease of collection and minimal discomfort, salivary diagnostics have gained increasing attention for reflecting systemic physiological and pathological conditions [20]. Recent research has begun to explore salivary vitamin D measurement and its correlation with periodontal disease parameters, suggesting saliva could serve as a valuable biomarker for periodontal health [21, 22].

To our knowledge, few studies have investigated the association between salivary vitamin D and periodontal status, particularly in the context of non-invasive biomarker research. This study contributes to the literature by examining this association within an Iranian population using a salivary diagnostic approach. The underlying hypothesis was that lower salivary vitamin D levels would be associated with increased disease severity.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This cross-sectional analytical study was conducted between July 2020 and July 2021 at the Department of Periodontology, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran. A total of 100 participants were enrolled, including 50 patients diagnosed with periodontitis and 50 periodontally healthy controls. The sample size was calculated using G*power version 3.1.9.7, based on data from a previous study by Wang et al. [23], with a significance level (α) of 0.05 and a statistical power (1–β) of 90%. According to their findings, the mean salivary vitamin D levels in the periodontitis and healthy groups were 19.09 ± 3.44 ng/mL and 23.82 ± 3.03 ng/mL, respectively. The calculation showed that at least 11 subjects per group were needed. To enhance statistical reliability and generalizability, 50 participants were included in each group.

The periodontitis group included individuals aged 18 to 65 years who presented with CAL≥ 3 mm and PPD≥ 4 mm in at least 2 teeth, according to the 2017 World Workshop classification criteria for periodontal diseases [1]. The control group consisted of systemically healthy individuals without clinical signs of periodontal disease (PPD ≤ 3 mm, no CAL, and bleeding on probing (BOP)).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Age between 18 and 65 years.

For the periodontitis group: clinical diagnosis as specified above.

For the control group: absence of history or clinical evidence of periodontitis.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Systemic conditions affecting vitamin D metabolism, such as renal, hepatic, or endocrine disorders.

Vitamin D supplementation within the previous 3 months.

Current smokers or tobacco users.

Pregnant or lactating women.

History of periodontal therapy or antibiotic use within the last 6 months.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Approval code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.236; Approval date: June 8, 2020). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for human research. Patients with periodontitis were offered and received standard non-surgical periodontal therapy (scaling and root planing) after saliva collection, in accordance with institutional treatment guidelines.

2.4. Saliva Collection and Processing

Unstimulated whole saliva samples were collected between 8:00 and 10:00 a.m. to minimize diurnal variation. Participants were instructed to avoid eating, drinking, smoking, or performing oral hygiene procedures for at least one hour before sample collection. Saliva was collected by passive drooling into sterile tubes over a 5-minute period. Immediately after collection, samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove cellular debris. The clear supernatants were aliquoted and stored at –80°C until further analysis.

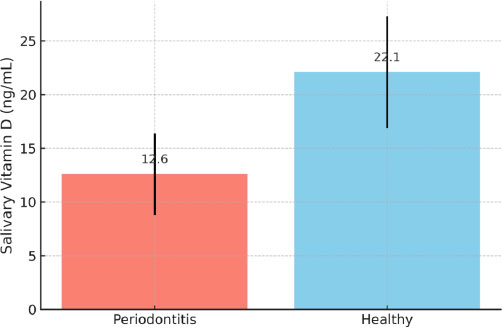

Comparison of mean salivary vitamin D levels between periodontitis and healthy participants. Error bars indicate standard deviation. The difference between groups was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

2.5. Measurement of Salivary Vitamin D

Salivary vitamin D concentrations were measured using a commercially available ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical, Michigan, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were tested in duplicate, and values were reported in ng/mL. The vitamin D ELISA kit used had an assay range of 0.5-200 ng/mL and a sensitivity of 0.25 ng/mL.

2.6. Clinical Periodontal Examination

A single calibrated examiner, blinded to the salivary vitamin D results, performed full-mouth periodontal examinations. Clinical parameters were recorded at six sites per tooth and included PPD, CAL, and BOP. Examiner calibration was conducted prior to data collection to ensure intra-examiner reliability, with an intra-class correlation coefficient exceeding 0.85.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS software version 16.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Between-group comparisons were conducted using independent samples t-tests for normally distributed data or Mann–Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed variables. Correlations between salivary vitamin D levels and clinical periodontal parameters (PPD, CAL, BOP) were evaluated using Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients as appropriate. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 100 participants were enrolled (50 with periodontitis and 50 healthy controls). No statistically significant differences in age or gender were observed between groups (p > 0.05), as summarized in Table 1.

3.2. Salivary Vitamin D Levels

The mean salivary vitamin D levels were significantly lower in the periodontitis group (12.6 ± 3.8 ng/mL) compared to the healthy group (22.1 ± 5.2 ng/mL; p < 0.01) Table 2. This difference is visually demonstrated in Fig. (1), which shows the group-wise comparison with standard deviation error bars.

| Characteristics | Periodontitis Group (n=50) | Control Group (n=50) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years (Mean ± SD) | 42.8 ± 8.5 | 41.6 ±9.2 |

| Gender, n (Male/Female) | 25/25 | 25/25 |

| Parameters | Periodontitis (Mean ± SD) | Control Group (Mean ± SD) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salivary Vitamin D (ng/ml) | 12.6 ± 3.8 | 22.1 ± 5.2 | P<0.01 |

| PPD (mm) | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | P<0.01 |

| CAL (mm) | 5.2 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | P<0.01 |

| BOP (%) | 35.4 ± 8.9 | 12.3 ± 4.5 | P<0.01 |

3.3. Periodontal Clinical Parameters

Patients with periodontitis exhibited significantly higher PPD (4.9 ± 1.2 mm), CAL(5.2 ± 1.4 mm), and BOP (35.4 ± 8.9%) than the control group (PPD: 2.0 ± 0.5 mm; CAL: 2.1 ± 0.4 mm; BOP: 12.3 ± 4.5%) (All p < 0.01), as shown in Table 2.

3.4. Correlation Analysis

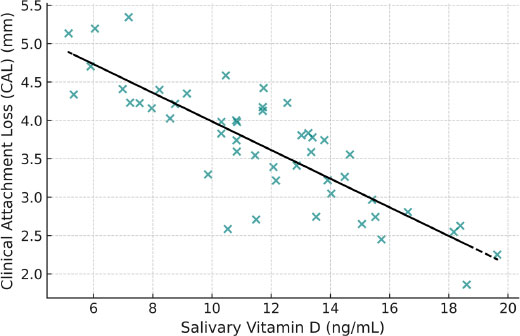

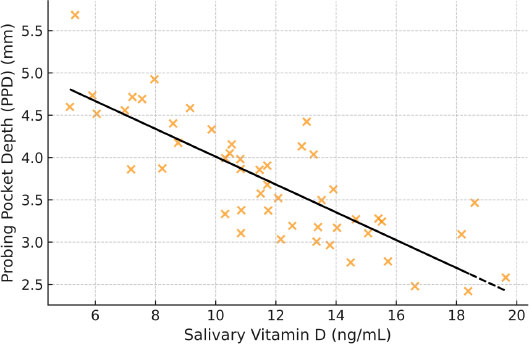

Spearman's correlation coefficients indicated moderate, statistically significant inverse relationships between salivary vitamin D levels and key clinical periodontal indicators:

PPD: r = –0.45, p < 0.01

CAL: r = –0.50, p < 0.01

BOP: r = –0.38, p < 0.05

These associations are illustrated in Figs. (2 and 3), which show moderate inverse relationships between salivary vitamin D levels and periodontal parameters, supporting the hypothesis that lower vitamin D levels are associated with increased periodontal disease severity.

4. DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that patients with periodontitis exhibited significantly lower salivary vitamin D levels compared with healthy controls, with inverse correlations observed between vitamin D and PPD, CAL, and BOP. These findings suggest that insufficient vitamin D availability within the oral environment may be linked to periodontal tissue breakdown.

Our results are consistent with earlier serum-based investigations. Dietrich et al. [11] reported that lower serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D was associated with greater gingival inflammation, while Antonoglou et al. [12] linked reduced serum 1,25(OH)2D to deeper probing depths and attachment loss. Similarly, Kim et al. [24] and Shirmohammadi et al. [25] found that vitamin D deficiency was associated with severe periodontitis and poorer post-treatment outcomes, while Saleh et al. [26] and Laky et al. [27] demonstrated associations between vitamin D deficiency, systemic inflammatory markers, and worse periodontal indices. Collectively, these findings support the role of vitamin D deficiency in promoting periodontal inflammation and tissue destruction. Our study extends these observations to saliva, showing that local vitamin D levels mirror systemic associations and reflect periodontal status.

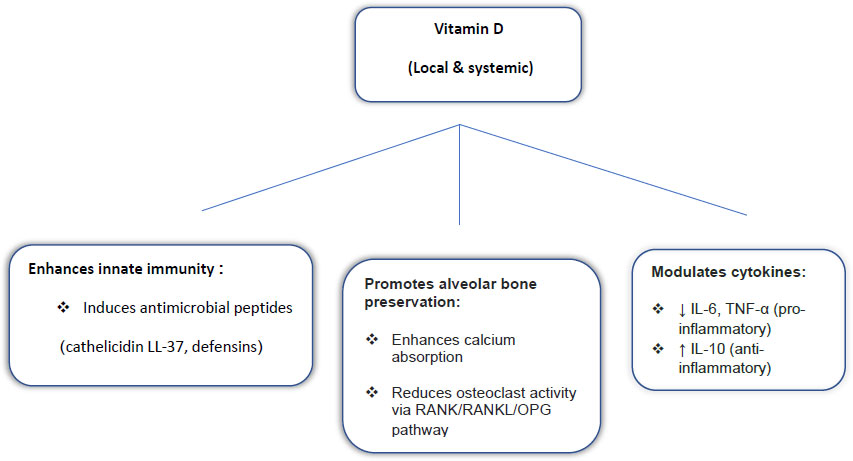

The biological plausibility of these findings is underpinned by vitamin D’s immunomodulatory and bone-regulating properties. Vitamin D enhances innate immunity through antimicrobial peptides such as cathelicidin (LL-37) and defensins [28, 29], regulates inflammation by downregulating IL-6 and TNF-α while upregulating IL-10 [30], and preserves alveolar bone by influencing calcium absorption and modulating the RANK/RANKL/OPG pathway [31, 32]. These mechanisms-schematically summarized in Fig. (4) illustrate how insufficient vitamin D may intensify periodontal inflammation and alveolar bone loss.

A notable strength of the present investigation is the use of saliva, a needle-free, non-invasive biological fluid that reflects the local oral microenvironment [22]. While most previous studies have assessed serum vitamin D [11-15, 24-27], salivary analysis may provide more immediate insights into periodontal conditions and holds promise for clinical application. Nonetheless, longitudinal and interventional studies are required to confirm causality and establish whether salivary vitamin D testing can be adopted as a reliable diagnostic or prognostic tool in periodontal practice.

5. STUDY LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design prevents causal inference; it remains unclear whether vitamin D deficiency contributes to the initiation and progression of periodontal disease or is a consequence of systemic and local inflammation. Second, potential confounders such as dietary intake, sun exposure, seasonality, physical activity, and skin pigmentation were not comprehensively assessed, which may have influenced salivary vitamin D levels. Third, the absence of concurrent serum vitamin D measurements limits comparison between systemic and salivary status. Fourth, the study population was derived from a single geographic location and ethnic group, which may restrict generalizability. Fifth, salivary vitamin D levels were not evaluated following periodontal therapy, which could have provided valuable insights into dynamic changes in response to treatment. Finally, baseline vitamin D status prior to disease onset was unavailable, complicating the interpretation of temporal and causal relationships.

Scatter plot showing the inverse correlation between salivary vitamin D levels and CAL. A moderate negative trend is evident (r = –0.50, p < 0.01).

Scatter plot demonstrating the inverse association between salivary vitamin D levels and PPD (r = –0.45, p < 0.01).

Proposed role of Vitamin D in periodontal health.

6. CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Conventional clinical indices such as PPD, CAL, and BOP remain the primary diagnostic tools for periodontal disease; however, salivary vitamin D assessment may provide complementary value at different stages of care: (1) Prevention: enabling non-invasive screening of at-risk individuals before overt clinical disease develops; (2) Management: monitoring vitamin D status as part of comprehensive periodontal therapy, potentially guiding adjunctive interventions; (3) Prognosis: providing supplementary prognostic information on the likelihood of disease progression alongside conventional indices.

With further validation, salivary vitamin D testing could be incorporated into chairside biomarker panels, enhancing diagnostic accuracy, supporting personalized treatment planning, and improving long-term periodontal outcomes in a patient-friendly manner.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that patients with periodontitis exhibited lower salivary vitamin D levels, which were inversely correlated with key clinical indicators of disease severity. These findings are consistent with previous serum-based research and are biologically plausible given vitamin D’s immunomodulatory and bone-preserving functions. Nevertheless, unmeasured confounding factors and the cross-sectional design warrant cautious interpretation. Longitudinal and interventional futures studies-particularly those evaluating vitamin D supplementation and incorporating rigorous multivariate analyses-are needed to clarify causality and determine whether salivary vitamin D can be established as a reliable diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in periodontal health and disease.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: P.M and M.F.: Conceptualized and designed the study; M.S.: Responsible for data collection; S.B and M.S.: Performed data analysis; P.M and M.F.: Drafted the initial manuscript. All authors critically revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| CAL | = Clinical Attachment Level |

| PPD | = Probing Pocket Depth |

| BOP | = Bleeding on Probing |

| ELISA | = Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| RANKL | = Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand |

| VDR | = Vitamin D Receptor |

| OPG | = Osteoprotegerin |

| STROBE | = Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| BMI | = Body Mass Index |

| IL-6 | = Interleukin-6 |

| TNF-α | = Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Approval code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.236; Approval date: June 8, 2020).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article will be available from the corresponding author [P.M] upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their gratitude to the participants and the staff of the Periodontology Department at Tabriz Dental School for their assistance and cooperation during the study.