All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Fracture Resistance of Anterior Teeth Restored with Y-TZP and Other Post/Core Systems Using Different Cements

Abstract

Introduction

Endodontically treated teeth often lose structural integrity, requiring post-and-core restoration. Advances in materials and CAD/CAM technology have enabled esthetic, custom-made restorations, such as one-piece yttrium tetragonal zirconia polycrystal (Y-TZP). This study compared the fracture resistance of different esthetic post-and-core systems using resin and glass ionomer cements.

Methods

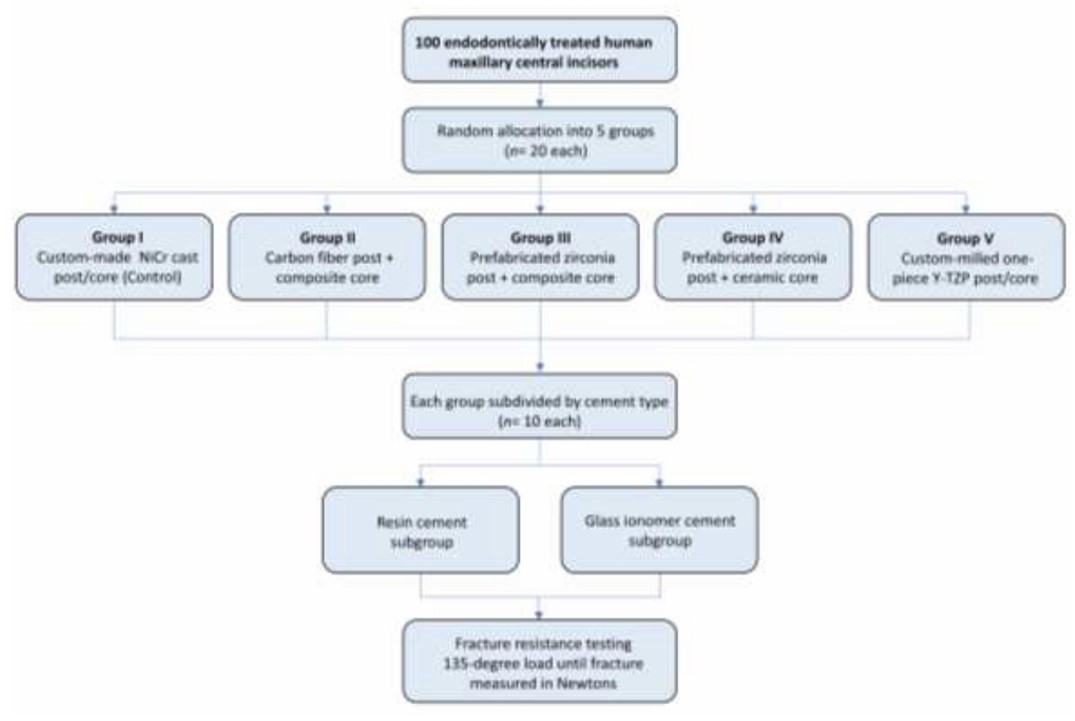

One hundred extracted human maxillary central incisors were endodontically treated and restored with five post-and-core systems: one-piece Y-TZP, cast metal (NiCr), carbon fiber, prefabricated zirconia with composite core, and prefabricated zirconia with ceramic core (n = 20). Each group was subdivided according to cement type: resin cement or glass ionomer cement. Specimens were restored with all-ceramic crowns and loaded at 135° until fracture. Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA (α = 0.05).

Results

Significant differences were observed among post systems and cement types (p < 0.001). The one-piece Y-TZP system showed the highest fracture resistance (1191.0 ± 85.6 N with resin cement), while the carbon fiber system showed the lowest values (375.4 ± 27.9 N with glass ionomer cement). Cement type significantly influenced most groups, except NiCr.

Discussion

The superior performance of the one-piece Y-TZP system may be attributed to its monolithic structure and high mechanical strength afforded by CAD/CAM fabrication, along with a more precise fit and improved stress distribution, which likely contributed to the enhanced mechanical performance. Resin cement generally enhanced fracture resistance compared with glass ionomer cement due to improved adhesion and retention.

Conclusion

One-piece Y-TZP posts demonstrated the highest fracture resistance. Resin cement generally improves fracture resistance compared with glass ionomer cement.

1. INTRODUCTION

The long history of success with cast posts and cores for restoring endodontically treated teeth was due to their superior physical and mechanical properties [1]. However, the dark shadows beneath translucent coronal restorations make them less visually appealing. This issue becomes more pronounced in patients with a high lip line, where the restorations are more visible. Furthermore, the high elastic modulus of cast post materials can lead to stress concentration in the radicular dentin, potentially resulting in root fractures. This risk is particularly concerning because it can lead to catastrophic failures that compromise the tooth’s long-term prognosis [2].

Prefabricated posts, including metal (titanium and stainless steel) and carbon fiber posts combined with composite resin cores, have been widely used for anterior restorations under esthetic crowns. While cast metallic posts and cores are more prone to causing root fractures, prefabricated metal posts combined with composite resin cores have shown a higher incidence of core failures [3, 4]. Carbon fiber posts have demonstrated fracture resistance comparable to that of prefabricated metal posts, but notably, without inducing root fractures [5].

Increased demand for tissue compatibility and aesthetics has led to the development of prefabricated, tooth-colored, and metal-free post-and-core systems. Prefabricated zirconia ceramic posts have been introduced for use in the esthetic zone, where their tooth-colored appearance helps preserve the overall esthetic outcome when used beneath translucent ceramic crowns. These systems have shown fracture resistance comparable to that of titanium and nickel-chromium cast posts [6-8]. Advances in porcelain adhesive bonding systems have further facilitated the integration of these posts with resin composite core materials. Additionally, systems combining zirconia posts with heat-pressed ceramic cores have been introduced and recommended as viable alternatives to traditional cast post-and-core restorations [8, 9].

In the early 1990s, yttrium tetragonal zirconium polycrystals (Y-TZP) were introduced into dentistry [10]. Owing to their excellent mechanical strength and biocompatibility, Y-TZP materials have been widely used in all-ceramic crowns and fixed partial dentures, as well as in various other dental applications [11]. To maintain the stability of zirconia in its pure form at room temperature, yttrium oxide is incorporated, producing a multiphase material referred to as partially stabilized zirconia. The distinct physical properties of this material contribute to its outstanding performance characteristics [12].

A novel method was developed to produce milled custom-made posts using CAD/CAM technology [13]. When applied to Y-TZP, this method enabled the creation of a one-piece post-and-core system that offered increased toughness, optimal canal adaptation, and ideal aesthetic qualities. This type of custom-made post-and-core restoration is particularly indicated for wide-flared endodontically treated teeth requiring all-ceramic crowns for esthetic reasons.

Although various post-and-core systems have been extensively studied, limited data exist on how the type of luting cement influences their performance, particularly in esthetic restorations. The choice between conventional glass ionomer cement and adhesive resin cement may significantly impact the fracture resistance of restored teeth, yet few studies have offered direct comparisons across different post systems. Therefore, the present study primarily aimed to investigate the effect of cement type on the fracture resistance of endodontically treated teeth restored with various esthetic post-and-core systems. Specifically, it evaluated how resin cement and glass ionomer cement influence the performance of one-piece zirconium post-and-core foundations, other esthetic alternatives, and cast metal restorations. The null hypotheses formulated for this study are as follows:

- No significant difference in fracture resistance exists between teeth restored with posts cemented with resin cement and those bonded with glass ionomer cement.

- No significant variation in fracture resistance is observed among different post-and-core systems, including one-piece zirconium post-and-core, cast-metal post-and-core, and other esthetic post-and-core foundation systems.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Teeth Selection and Preparation

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee at King Abdulaziz University, under reference number 25-02-25. Human maxillary central incisors were obtained from oral surgery clinics for this study. Hand-scaling instruments were used to remove any hard or soft deposits. Teeth with fractures, cracks, or caries were excluded. The internal structure of the teeth was assessed using buccolingual and mesiodistal radiographs. Any teeth exhibiting root resorption, fractures, or canal obstructions were eliminated. Only teeth with a single, intact root canal were considered for inclusion. Selected teeth were stored in distilled water at 37°C with thymol crystals for preservation. A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1.9.7 to determine the required sample size for a two-way ANOVA with fixed effects, considering 10 groups (5 main groups, each with 2 subgroups). The analysis was based on a medium effect size (f = 0.4), an alpha error probability of 0.05, and a desired power of 0.80. The analysis indicated that a total of 100 samples would be required to detect statistically significant differences among the groups.

To ensure uniformity, teeth with a root length of 15 ±1 mm and mesiodistal and buccolingual dimensions within 10% of the mean were chosen. The teeth were decoronated, leaving 2.5 mm of coronal tooth structure above the cementoenamel junction on the proximal surfaces, maintaining a perpendicular orientation to the root’s long axis. This was accomplished using a diamond disc attached to a straight handpiece (Kavo Ltd, Amersham, UK) under continuous water irrigation.

Endodontic treatment was carried out on all selected teeth. The canals were cleaned and shaped using the step-back technique, with instrumentation extending to the working length of a size 40 K-file (Union Broach, NY, USA), terminating 1 mm short of the apex. The middle and coronal thirds of the roots were further prepared with K-files ranging from #45 to #70. To maintain apical patency, a #10 K-file was passed through the apical foramen. Throughout the procedure, irrigation with 2 mL of a 5.25% sodium hypochlorite solution was performed after the use of each file. Standardized gutta-percha cones (PD Vevey, Switzerland), extending to the whole working length with a “tug-back” fit, were cemented with AH-26 sealer. A finger spreader was used to compact the material, followed by the insertion of non-standardized gutta-percha cones until the canal was completely filled using a cold compaction approach. The specimens were then immersed in distilled water for 24 hours to allow for complete sealer setting. Post space preparation was performed by removing gutta-percha from the canal using Gates-Glidden burs sizes 2, 3, and 4, ensuring that 4-5 mm of material remained in the apical region.

2.2. Experimental Grouping and Restorative Procedures

The prepared teeth were randomly distributed into five experimental groups according to the type of post-and-core system used for restoration, with each group consisting of 20 specimens (n=20).

- Group I (NiCr-Control): Cast metal post-and-core composed of a nickel-chromium alloy (Wiron 99; BEGO, Bremen, Germany).

- Group II (CF-C): Carbon fiber posts (Bisco Inc, Schaumburg, IL, USA) paired with composite resin cores.

- Group III (ZrO2-C): Prefabricated zirconium dioxide posts (CosmoPost; Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) combined with composite resin cores.

- Group IV (ZrO2-Cer): Prefabricated zirconium dioxide posts (CosmoPost) incorporated with ceramic cores (IPS Empress Cosmo Ingot; Ivoclar Vivadent).

- Group V (Y-TZP): Custom-milled one-piece Y-TZP post and core (Cercon; DeguDent GmbH, Hanau-Wolfgang, Germany).

Each group was subdivided into two smaller subgroups (n=10) based on the type of cement used for post cementation: adhesive resin cement (Panavia, Kuraray Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) or glass ionomer cement (Ketac-Cem, 3M ESPE, AG, Seefeld, Germany) (Fig. 1).

Post space preparation consistency was maintained by using pre-shaped and finishing drills corresponding to the post size no. 3 (Bisco Inc, Schaumburg, IL 60193, USA). For all groups, a ferrule with a width of 1 mm and height of 2 mm was prepared using a tapered flat-end diamond bur mounted on a high-speed handpiece with a coolant (Kavo Ltd, Amersham, UK). A plastic tube was placed around the bur shank to limit the ferrule preparation to 2 mm.

Study design and experimental grouping.

(A) The resin patterns of the posts and cores were attached to the scanning ring horizontally. (B) The patterns were painted with silver paint to be easily scanned. (C) A yttrium tetragonal zirconium polycrystals (Y-TZP) ceramic block was milled to produce Y-TZP posts and cores based on scans of the resin pattern.

For group I, the posts were prepared as follows: the canals were injected with a separating medium (Die Lube; Degussa-Ney Dental Inc., Bloomfield, Connecticut). The plastic post was painted with pattern resin (GC pattern resin, GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) using a brush, inserted into the canals before setting, and left without disturbance for 10 seconds. Then, the plastic post carrying the resin was pumped in and out of the canal to ensure a passive fit until the pattern resin was fully set. Pattern resin was added to the coronal portion of the plastic post to build up the core, taking the shape and size of a prepared all-ceramic crown using a maxillary central incisor preformed mold (Build-It kit, Jeneric/Pentron, Wallingford, CT 06492, USA) for standardization of core buildup [14]. Finished post-and-core patterns were invested, burned out, and cast into a nickel-chromium alloy (Wiron 99; BEGO, Bremen, Germany).

For group II, the root canals were drilled as mentioned to suit Bisco post no. 3. The fiber posts were placed into the canal and cemented using the cement specified for each subgroup. The excess post was cut. The core was built up on the coronal portion of the fiber post with microhybrid composite resin (Z100, 3M-ESPE, USA) using the specified preformed mold described in group I.

For group III, a 1.7 mm prefabricated zirconia post (Cosmopost; Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) was delivered using similar steps to those in group II, and a composite core was built up.

For group IV, the zirconia post space was drilled, as mentioned. A 1.7 mm prefabricated zirconia post (Cosmopost) was painted with pattern resin and placed into the root canal. The core was built up by pattern resin, as mentioned in group I. Each post/core was sprued, invested, and pressed using Empress Cosmo ingots (Ivoclar Vivadent).

For group V, a post/core pattern was made as in group I (Fig. 2A); however, instead of investing and casting it in metal, the pattern was silver-painted and scanned (Fig. 2B), then milled from zirconia blocks and sintered using the Cercon System (DeguDent GmbH, Hanau-Wolfgang, Germany) (Fig. 2C).

After post-and-core cementation, impressions were taken using addition silicone (Reprosil, Caulk/Dentsply, USA), and master dies were constructed. All-ceramic crowns were then fabricated using Y-TZP Cercon material (DeguDent GmbH, Hanau-Wolfgang, Germany) and cemented with resin cement onto the corresponding teeth.

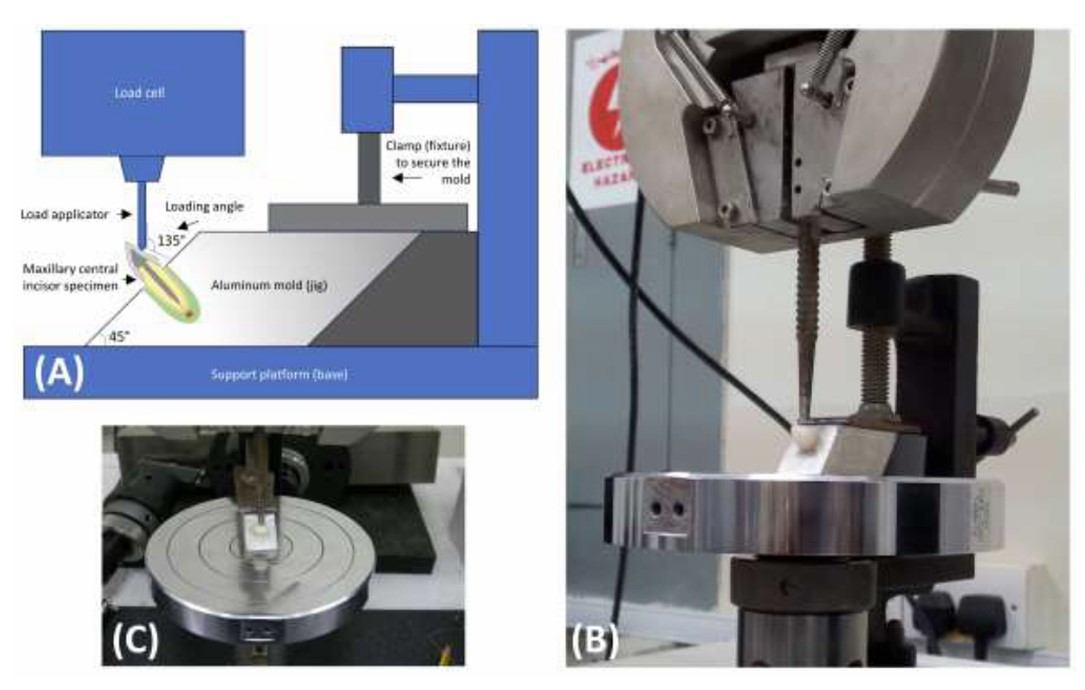

2.3. Jig Fabrication and Mechanical Testing

A jig was created from a ¾ inch square cross-section aluminum rod, cut into small rods with one end at 90 degrees and the other at a 45-degree angle. A perpendicular hole on the external surface (diameter = 8 mm) was drilled in the angled end to accommodate the root of a tooth specimen. A thin layer of light body addition silicon impression material (Reprosil, Caulk/Dentsply, USA) was applied to the root surfaces to provide a cushioning effect simulating the periodontal ligament. Each crowned tooth was secured in the hole with a ball of periphery wax at the root tip. Autopolymerizing acrylic resin (SR-Ivolen, Ivoclar, Schaan, Liechtenstein) was poured into the hole to embed the root to the desired height, simulating the bone crest level (Fig. 3A).

The prepared specimens were attached to an Instron Universal Testing Machine (Model 1193, Instron Limited, UK) (Fig. 3B). The load was directed to the middle of the lingual surface of each crown at a 135-degree angle and a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min until fracture occurred, and the maximum load in Newtons (N) was recorded (Fig. 3C).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS software version 20 (IBM Inc., USA). Assumptions of normality, independence, homogeneity of variance, and homoscedasticity were assessed, and outliers were identified. Descriptive statistics were calculated, and a two-way ANOVA was conducted to evaluate differences in fracture resistance loads by post system and cement type. Further analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test. An independent samples t-test was used to compare the two cement types within each post system. All statistical tests were conducted at a significance level of α = 0.05.

Fracture resistance test setup: (A) Schematic illustration showing the positioning of the sample inside the aluminum mold. The jig surface is inclined at 45º to the base, resulting in a loading angle of 135º relative to the long axis of the tooth, simulating the natural loading angle of anterior teeth. (B) Side view showing the aluminum mold containing the sample securely clamped to the table of the mechanical testing machine, with the load applied to the sample via a metal rod. (C) Frontal view of the mounted sample.

3. RESULTS

The two-way ANOVA (Table 1) indicated significant effects of both post type (p < 0.001) and cement type (p < 0.001) on fracture resistance. However, the interaction between post and cement type did not significantly affect the fracture resistance (p = 0.563).

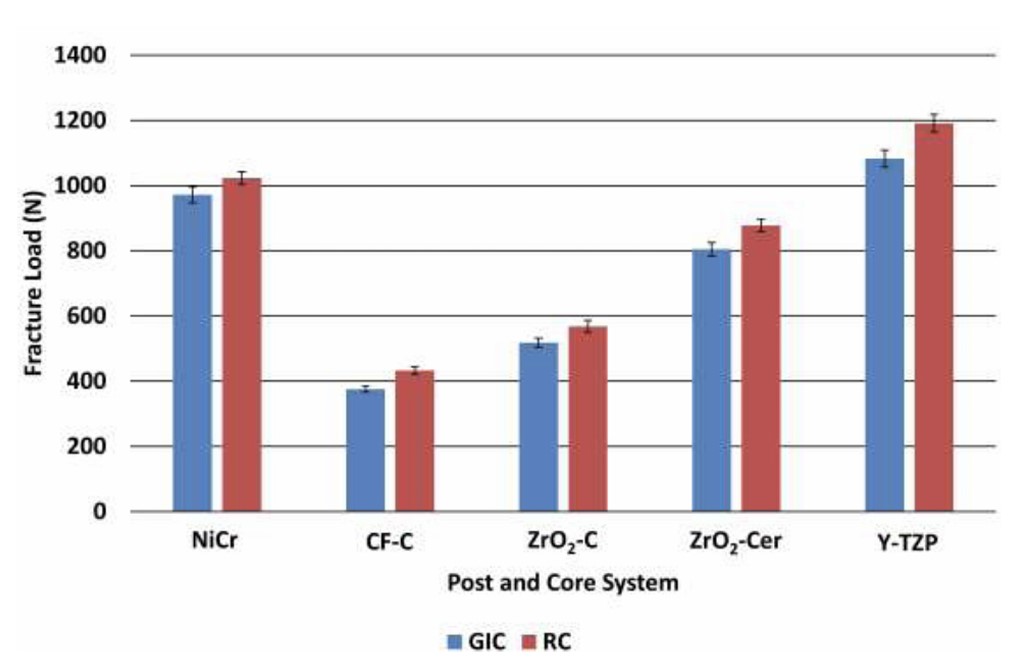

In the control group, NiCr posts exhibited fracture loads of 971.8 N with GIC and 1022.9 N with RC, with no significant differences between them (p=0.123). CF-C posts recorded lower fracture loads of 375.4 N with GIC and 433.2 N with RC, with a statistically significant difference between the subgroups (p = 0.001). ZrO2-C posts had fracture loads of 517.9 N with GIC and 567.9 N with RC, with a significant difference in fracture resistance with GIC (p = 0.048). ZrO2-Cer posts showed fracture loads of 804.1 N with GIC and 878.1 N with RC, also displaying a statistically significant difference (p = 0.019). The highest fracture loads were observed with Y-TZP posts, which had 1082.5 N with GIC and 1191.0 N with RC, with significant differences between the two cements (p = 0.010) (Table 2 and Fig. 4).

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df * | Mean Square | F ** | p-value | Partial Eta Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | 7638728.360 | 9 | 848747.596 | 212.189 | 0.000 | 0.955 |

| Intercept | 61540887.040 | 1 | 61540887.040 | 15385.367 | 0.000 | 0.994 |

| Post | 7510226.860 | 4 | 1877556.715 | 469.394 | 0.000 | 0.954 |

| Cement | 116553.960 | 1 | 116553.960 | 29.139 | 0.000 | 0.245 |

| Post × Cement | 11947.540 | 4 | 2986.885 | 0.747 | 0.563 | 0.032 |

| Error | 359996.600 | 90 | 3999.962 | - | - | - |

| Total | 69539612.000 | 100 | - | - | - | - |

| Corrected Total | 7998724.960 | 99 | - | - | - | - |

| Post and Core System | Fracture Load (N) | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GIC | RC | ||

| NiCr (control) | 971.8 (77.5)a | 1022.9 (63.1)a | 0.123 |

| CF-C | 375.4 (27.9)b | 433.2 (36.8)b | 0.001 |

| ZrO2-C | 517.9 (46.9)c | 567.9 (57.8)c | 0.048 |

| ZrO2-Cer | 804.1 (65.4)d | 878.1 (62.5)d | 0.019 |

| Y-TZP | 1082.5 (82.3)e | 1191.0 (85.6)e | 0.010 |

| P-value** | <0.001 | <0.001 | - |

** P-values derived from one-way ANOVA testing of the different post and core systems.

Mean fracture load values (in Newtons) with standard error (error bars) for the different post and core system groups. GIC and RC refer to glass ionomer cement and resin cement, respectively. NiCr, CF-C, ZrO2-C, ZrO2-Cer, and Y-TZP represent the following systems: nickel–chromium cast metal post-and-core, carbon fiber posts with composite resin core, prefabricated zirconia posts with composite resin core, prefabricated zirconia posts with ceramic core, and custom-milled one-piece Y-TZP post-and-core, respectively.

4. DISCUSSION

Various techniques have been introduced to advance one-piece, CAD/CAM-fabricated, customized post-and-core systems, including both semi-digital indirect workflows and fully digital direct approaches using a variety of tooth-colored materials [15-17]. Several studies have investigated the fracture resistance of various esthetic one-piece custom post materials compared with prefabricated and conventional cast post-and-core systems, with variable results [18-22]. These studies have predominantly used adhesive resin cements, which are favored for their superior bond strength; however, conventional cements, such as glass ionomer cements (GICs), offer the important clinical advantage of retrievability, a critical factor in managing potential restoration failures. Despite this relevance, there is a notable lack of literature directly comparing the performance of conventional versus adhesive resin cements across different post systems.

In the current study, specific measures were taken to simulate clinical conditions, thereby supporting the validity of the experimental methodology. The cushioning effect of the periodontal ligament was replicated by using a silicone impression material as a spacer around the root. Additionally, the load was applied at an angle of 135º to the middle of the lingual surface of each crown, corresponding to the typical occlusal contact area and loading angle experienced by maxillary central incisors during function.

The null hypothesis was rejected due to significant differences in fracture resistance among the various post-and-core systems and between the two types of cement investigated in this study. Although the fracture resistance values differed significantly across all groups, all systems, regardless of the cement used, exhibited values well above the maximum biting force typically exerted by a maxillary central incisor, which is approximately 150 N [23].

The highest fracture load values were observed with the one-piece custom Y-TZP post-and-core system, followed by the control custom NiCr post-and-core system. These findings are in line with previous research on the fracture strength of root canal-treated mandibular premolars restored with different post systems, including one-piece cast-metal and zirconia posts combined with all-ceramic crowns [24]. The significantly higher fracture resistance observed with the zirconia system compared to the metal cast post may be attributed to the absence of defects and porosities commonly associated with the casting process of NiCr alloys. In contrast, the milling process used to fabricate the zirconia posts results in a more precise fit and improved stress distribution, which likely contributed to the enhanced mechanical performance. Notably, milled zirconia posts have been shown in previous finite element analyses to exhibit a stress distribution pattern comparable to that of gold posts, indicating favorable biomechanical behavior [25].

In the present study, it was observed that one-piece systems, whether fabricated by CAD/CAM milling or metal casting, demonstrated fracture resistance values of approximately 1000 N or higher. In contrast, systems composed of non-homogeneous post-and-core materials exhibited lower fracture resistance, typically below 1000 N. These latter systems utilized prefabricated posts combined with cores made from different materials, such as hot-pressed ceramic or directly built-up composite resin, involving distinct fabrication techniques. This suggests that greater material homogeneity and compatibility between the post and core components may contribute to improved mechanical performance. This trend was particularly evident in Group IV, where teeth were restored with prefabricated zirconia posts and heat-pressed ceramic cores with relatively similar material properties. While this system performed well, its fracture resistance was significantly lower than that of the entirely homogeneous one-piece systems, a finding consistent with previous research [19].

The fracture resistance values of the one-piece zirconia post-and-core systems in the present study (exceeding 1000 N) were found to be notably higher than those reported in previous studies, which typically reported much lower values. For example, one study on maxillary central incisors with a similar experimental setup reported fracture resistance of approximately 450 N for one-piece zirconia posts, substantially lower than the values observed in our study [26]. Notably, that study did not specify whether coronal coverage was used, which may explain the lower values, as the presence of a crown can enhance fracture resistance through the ferrule effect [27]. Similarly, another study testing post systems in premolars without coronal coverage reported fracture loads below 400 N [28]. In another study, zirconia post systems in premolars demonstrated lower fracture resistance (~430 N) than fiber posts with ceramic crowns, despite all being luted with resin cement [21]. In that study, adjustments were made to the zirconia posts to fit the canal, potentially introducing microcracks and compromising structural integrity. Additionally, one study reported fracture resistance values of approximately 440 N for zirconia post-and-core systems fabricated using custom CAD/CAM techniques [19]. This study included thermocycling, which may have contributed to lower fracture resistance values than those observed in our findings. Other contributing factors may include the use of larger resin dies for specimen stabilization and the strict standardization of post and radicular dentin dimensions within each group, which are variables not consistently reported or controlled in previous studies.

One of the primary objectives of this study, which has not been sufficiently addressed in the existing literature, was to compare the fracture resistance of different post systems when luted with either conventional glass ionomer cement or adhesive resin cement. The results demonstrated that the use of adhesive resin cement significantly enhanced fracture resistance across all post systems, particularly in the carbon fiber post group, which showed an approximate 15% increase in fracture strength. The cast NiCr group was the exception, exhibiting only a modest improvement. This finding supports the strengthening effect of resin cement, consistent with previous clinical and laboratory studies on ceramic restorations, which have shown that adhesive cementation with dentin bonding agents significantly improves fracture resistance and long-term survival rates [29, 30].

One of the main limitations of this study is the lack of data on fracture modes, such as whether failures occurred in the root, post, or crown. Identifying the type and location of fractures, restorable versus catastrophic, would have provided more profound insight into the failure behavior of the tested systems. However, the study was specifically designed to assess fracture resistance values, and no fractographic analysis was performed. Despite this, fracture strength alone remains a critical parameter, offering meaningful information about the mechanical performance and potential clinical success of restorative systems.

Future research should incorporate failure mode analysis to distinguish between restorable and non-restorable fractures, enhancing the clinical relevance of such findings. Further investigations might also explore one-piece systems with other materials, including milled or 3D-printed posts and cores, as well as variations in luting cement types and thicknesses. Additionally, dynamic mechanical loading with thermocycling and simulated chewing should be considered to better replicate intraoral conditions.

CONCLUSION

One-piece custom Y-TZP post-and-core foundations demonstrated the highest fracture resistance among the systems. Adhesive cementation significantly increased fracture resistance, particularly in the carbon fiber post system. Based on the findings of this study, to maximize strength, custom one-piece Y-TZP zirconia posts combined with adhesive resin cementation are recommended, especially in cases where higher clinical loads are anticipated. However, when retrievability is a priority, conventional glass ionomer cementation still provides adequate fracture resistance.

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

The current study helps practitioners select the highest-strength esthetic posts and cores and choose either the highest-strength adhesive or retrievable glass ionomer cements according to the case.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: M.M.A and T.Y.M.: Conceptualization; R.Z.A.: Formal analysis; M.A.A. and T.Y.M.: Funding acquisition; M.A.A. and T.Y.M.: Investigation; M.A.A and T.Y.M.: Methodology; M.A.A. and T.Y.M.: Resources; M.A.A., T.Y.M. and R.Z.A.: Visualization; M.A.A., T.Y.M. and R.Z.A.: Writing the original draft; M.A.A., T.Y.M. and R.Z.A.: Writing, reviewing, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| Y-TZP | = Yttrium Tetragonal Zirconia Polycrystal |

| GICs | = Glass Ionomer Cements |

| ANOVA | = Analysis of Variance |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

All procedures involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry at King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia (Reference No. 25-02-25).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article is available in the Zenodo repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18231608, reference number 10.5281/zenodo.18231608.

FUNDING

This study is financially supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (Grant/contract number 052/428 – 2008).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, for its financial support. They would also like to thank Prof. Mona Hasan for her contribution to the statistical analysis.