All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

An In Vitro Evaluation of the Antibacterial and Remineralizing Efficacy of a Silver Nanoparticle-Containing Toothpaste

Abstract

Introduction

This in vitro study aimed to compare the antibacterial action and microhardness effect on enamel of a toothpaste containing silver nanoparticles (SNPs) with three other preparations.

Methods

Four types of toothpaste were tested: one containing SNPs, one without SNPs, a probiotic toothpaste, and Signal toothpaste. Antibacterial activity against Streptococcus mutans was assessed using disc diffusion, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) assays. To evaluate remineralization, 40 extracted human third molars underwent pH cycling for one week, followed by Vickers hardness testing. Antibacterial results were analyzed with the Kruskal-Wallis test, and remineralization data with repeated measures ANOVA and Games-Howell post-hoc tests (α = 0.05).

Results

Signal toothpaste showed significantly smaller inhibition zones compared to the other three groups (p < 0.05). The SNP-toothpaste exhibited the lowest MBC, indicating the strongest bactericidal effect, while the control toothpaste with no SNPs showed the weakest activity (highest MIC and MBC). No significant differences in enamel microhardness were observed among the four groups after treatment (p > 0.05).

Discussion

The SNP-containing toothpaste demonstrated greater bactericidal efficacy against S. mutans, but its effect on enamel surface hardness was similar to the other fluoridated toothpastes.

Conclusion

SNP toothpaste showed superior antibacterial activity but did not improve enamel hardness beyond other fluoride-containing toothpastes.

1. INTRODUCTION

Dental caries is one of the most prevalent chronic diseases globally, infecting most of the world's population [1]. Dental caries is a multifactorial disease that starts with the fermentation of dietary carbohydrates by cariogenic bacteria, primarily Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans). The bacterium is found attached to the tooth surface and excretes organic acids that lead to the demineralization of dental hard structures, which in turn leads to the formation of carious lesions [2-4].

For decades, fluoride has remained the cornerstone of caries prevention, and the use of fluoride-containing toothpaste has been largely responsible for the decline in caries prevalence across many nations [5]. Fluoride exerts its cariostatic effect through multiple mechanisms: promoting enamel remineralization via formation of acid-resistant fluorapatite, lowering the critical pH for enamel dissolution, and inhibiting bacterial enzymes essential for acid production [6-8]. As a search for novel oral care agents, silver nanoparticles (SNPs) have been proposed as a strong antimicrobial agent. Silver has been a broad-spectrum antimicrobial compound for centuries, and its effectiveness is significantly improved when in the form of a nanoparticle with a high surface-area-to-volume ratio [9]. Bactericidal action of SNPs is due to thiol group binding of bacterial proteins and phospholipids, thereby causing membrane and cell damage. SNPs can also enter bacterial cells and inflict damage to their DNA [10, 11]. The good in vitro activity against S. mutans, including biofilm, has been well reported [12-14]. In addition, nano-silver has also been proposed as a non-staining alternative to silver diamine fluoride and may have an edge in occluding dentinal tubules to minimize hypersensitivity [15, 16].

Even though the antibacterial properties of SNPs are promising, the effectiveness of these when they are incorporated into a complete toothpaste formulation with fluoride and other ingredients is not clearly explained. Moreover, their efficacy has not yet been compared with other contemporary formulations, such as probiotic toothpastes, in the existing literature. Therefore, this research was designed to bridge this gap. The objective of this in vitro study was to evaluate 1- the antibacterial activity of a toothpaste containing SNPs against Streptococcus mutans using disc diffusion, MIC, and MBC assays, and 2- its effect on enamel surface microhardness, measured using Vickers hardness testing after a pH-cycling challenge. These outcomes were compared with three control formulations: a toothpaste without SNPs, a probiotic toothpaste, and a standard commercial product

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This in vitro study was conducted to compare the antibacterial and remineralizing properties of four commercially available toothpastes. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Research Institute of Dental Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Approval No: IR.SBMU.DRC.REC.1401.053), and adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, as applicable to research involving human biological material.

Four over-the-counter toothpastes were selected (Table 1). The SNP-containing and control formulations were obtained from the same manufacturer to ensure identical base composition, thereby isolating the effect of silver nanoparticles.

A sample size of n = 10 per group was calculated using PASS 15 (NCSS, LLC, USA) for a one-way ANOVA, with α = 0.05, power = 80 %, and an effect size of 0.6675. This effect size represents a moderate-to-large expected difference between groups, based on preliminary data.

Streptococcus mutans (PTCC 1683) was obtained from the Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology (IROST). For the agar disc diffusion assay, toothpaste samples were cast into a plexiglass mold (5 mm diameter, 2 mm depth), leveled, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and freeze-dried for 24 h to produce uniform solid discs. An S. mutans suspension equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard (≈ 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL) was used to inoculate Mueller–Hinton agar plates. Discs were placed onto the inoculated agar and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The diameter of the growth inhibition zone was measured in millimeters using a digital caliper. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) were determined using the broth microdilution method according to CLSI guidelines [17]. Two-fold serial dilutions of each toothpaste (51.2–0.025 mg/mL) were prepared in Mueller–Hinton broth in sterile 96-well plates. Wells were inoculated with S. mutans to a final concentration of 106 CFU/mL and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. MIC was defined as the lowest concentration showing no visible growth. For MBC determination, 100 µL from wells without visible growth were subcultured onto Mueller–Hinton agar and incubated for 48 h; MBC was defined as the lowest concentration producing a ≥ 99.9 % reduction in colony count.

| Group Name | Product Name | Manufacturer | Key Composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNP Group | Prodentin Nanosilver | Pars Hayan, Tehran, Iran | 1450 ppm fluoride, 20 ppm silver nanoparticles, zinc citrate |

| Control Group | Prodentin (Custom) | Pars Hayan, Tehran, Iran | 1450 ppm fluoride, zinc citrate (no SNPs) |

| Probiotic Group | Prodentin Probiotic | Pars Hayan, Tehran, Iran | 1450 ppm fluoride, Lactobacillus, zinc citrate |

| Commercial Group | Signal Complete 8 | Unilever, Tehran, Iran | 1450 ppm fluoride (no zinc citrate) |

Forty sound, non-carious human third molars extracted for reasons unrelated to this study were cleaned of soft tissue, stored in 2 % thymol solution for 48 h, and thereafter kept in distilled water at 4 °C until use. Each tooth was embedded in cold-cure acrylic resin with the buccal enamel surface exposed, then flattened and polished with 800- and 1000-grit silicon carbide papers to produce a standardized, flat enamel window. Baseline surface microhardness was measured using a Vickers hardness tester (Zwick Roell, Germany) with a 100 g load applied for 15 s; three indentations were made per specimen, and the mean was recorded as the Vickers Hardness Number (VHN). The pH-cycling protocol simulated alternating demineralization and remineralization phases. The demineralizing solution consisted of 2.2 mM CaCl2, 2.2 mM KH2PO4, and 0.05 M acetic acid, adjusted to pH 4.5 with NaOH. The remineralizing (artificial saliva) solution contained 1.5 mM CaCl2, 0.9 mM KH2PO4, 150 mM KCl, and 20 mM HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.0. Solutions were freshly prepared, and their pH was verified before each use with a calibrated digital pH meter [18] After demineralization, VHN measurements were repeated to confirm lesion formation. Specimens were randomly allocated into four groups (n = 10 per group). For 7 days, twice daily, a 1-cm strip of the assigned toothpaste was applied to the enamel surface using a soft-bristled brush for 5 min, followed by rinsing. Between treatment periods, samples were stored in fresh artificial saliva, replaced every 24 h. After the 7-day treatment regimen, post-treatment microhardness was measured using the same Vickers protocol (100 g, 15 s, three indentations per specimen) and the mean VHN recorded for each time point.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with α = 0.05. Data normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances with Levene’s test. Inhibition zone diameters, which were not normally distributed, were compared among groups using the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Games–Howell post-hoc comparisons. Microhardness values were analyzed using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA, with “Time” (baseline, post-demineralization, post-treatment) as the within-subject factor and “Toothpaste Group” as the between-subject factor.

3. RESULTS

The antibacterial properties of the four toothpastes against Streptococcus mutans were evaluated using three methods.

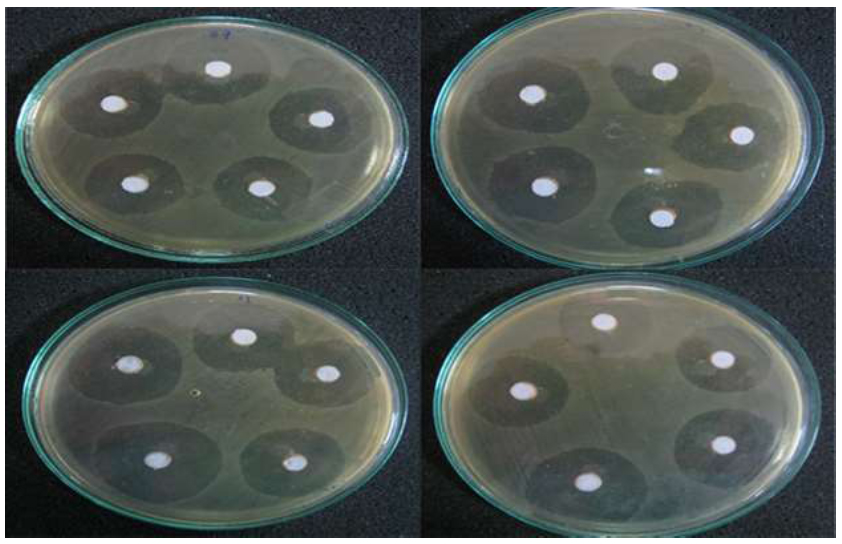

In the agar disc diffusion test, all formulations produced measurable zones of growth inhibition (Table 2). A significant difference was found among the groups (Kruskal–Wallis test, p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis showed that the inhibition zone produced by the Commercial (Signal) toothpaste was significantly smaller than those of the SNP, Control, and Probiotic groups. No statistically significant differences were observed among the latter three groups (Fig. 1).

| Toothpaste Group | Mean Inhibition Zone (mm) ± SD |

|---|---|

| SNP Group | 29. 60 ± 2.36 ᵃ |

| Control Group | 28. 00 ± 1.24 ᵃ |

| Probiotic Group | 29. 30 ± 1.05 ᵃ |

| Commercial Group (Signal) | 25. 70 ± 1.25 ᵇ |

Representative images of the agar disc diffusion test.

MIC and MBC values are presented in Table 3. The Control toothpaste (no SNPs) exhibited the highest MIC (400 µg/mL) and MBC (1600 µg/mL) values, indicating the weakest antibacterial performance. In contrast, the SNP-containing toothpaste demonstrated the strongest bactericidal activity, with the lowest MBC value (400 µg/mL).

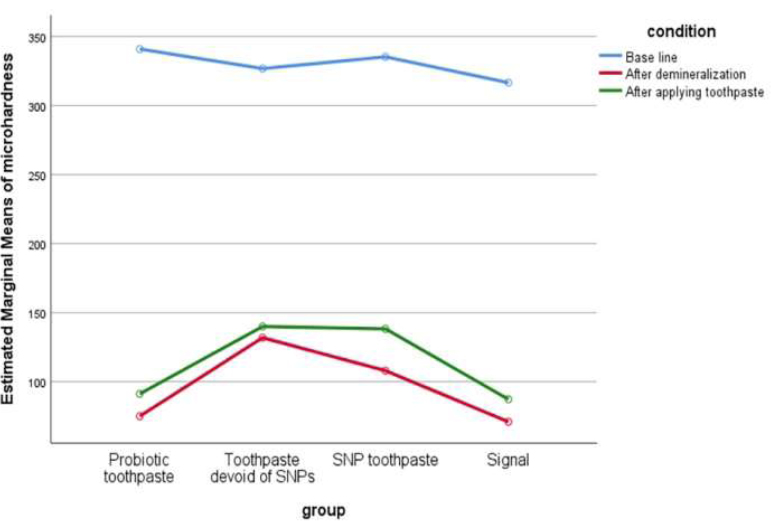

Mean Vickers Hardness Numbers (VHN) for the three measurement points are shown in Table 4. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a highly significant effect of time (p < 0.001), confirming that the demineralization and treatment cycles significantly altered enamel microhardness. There was no significant main effect of toothpaste type (p = 0.367) and no significant interaction between toothpaste group and time (p = 0.456).

| Test | SNP Group | Control Group | Probiotic Group | Commercial Group (Signal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (µg/mL) | 200 | 400 | 200 | 200 |

| MBC (µg/mL) | 400 | 1600 | 800 | 800 |

| Group | Baseline | After Demineralization | After Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNP Group | 329. 3 ± 35.2 | 102. 0 ± 86.4 * | 132. 3 ± 108.1 *, † |

| Control Group | 320. 8 ± 57.9 | 125. 0 ± 92.8 * | 134. 0 ± 94.4 *, † |

| Probiotic Group | 335. 0 ± 67.6 | 69. 0 ± 57.7 * | 85. 2 ± 58.9 *, † |

| Commercial Group | 310. 6 ± 62.4 | 65. 0 ± 83.2 * | 81. 3 ± 80.8 *, † |

† Significant difference compared to demineralized value for that group (p < 0.001).

Line graph illustrating the change in mean enamel microhardness for all four groups across the three experimental stages.

As illustrated in Table 4 and Graph 1, all four groups followed the same pattern: a marked decrease in VHN after demineralization, followed by an increase after the 7-day treatment period. However, post-treatment microhardness values in all groups remained below their respective baseline levels. At none of the three time points (baseline, post-demineralization, post-treatment) were statistically significant differences detected between the toothpaste groups.

The composite image shows the zones of growth inhibition against S. mutans for the different toothpaste groups. (A) SNP Group, (B) Control Group, (C) Probiotic Group, (D) Commercial Group (Signal).

The y-axis represents the Estimated Marginal Means of Microhardness. A high-resolution version of this graph has been provided.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated that toothpaste containing 20 ppm silver nanoparticles (SNPs) inhibited Streptococcus mutans more effectively than both its control formulation and a commercial comparator. However, the addition of SNPs did not produce any measurable improvement in enamel surface microhardness compared with other fluoride formulations subjected to pH-cycling, beyond the protective effect attributable to fluoride.

The antibacterial properties of the tested toothpastes were evaluated using two complementary methods. In the agar disc diffusion assay, the three products from the same manufacturer (SNP, control, and probiotic) produced similar inhibition zones, all substantially larger than those of the Signal toothpaste. This difference may be related to the presence of zinc citrate—an established antibacterial agent [15]—in the former three formulations. It should be noted that the disc diffusion method can underestimate the efficacy of agents with limited diffusion in solid media, such as nanoparticles [16]. To address this limitation, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) assays were performed in liquid broth, which allows better nanoparticle dispersion and ion release [19]. These results were more definitive: the SNP-free control required the highest concentrations for inhibition and bactericidal activity, whereas the SNP-containing toothpaste exhibited the lowest MBC, confirming its enhanced antibacterial effect. This observation is consistent with the findings of Teixeira et al. [20], who also reported lower MBC values for SNP-containing toothpaste compared with a conventional sodium fluoride formulation.

With respect to enamel surface microhardness, no significant differences were observed among the four groups after the treatment period. This outcome is likely due to two main factors. First, all toothpastes contained fluoride at a high concentration (1450 ppm), and its well-established mechanism—formation of acid-resistant fluorapatite—may have masked any minor additive effects of other ingredients [21]. Second, the SNP concentration used (20 ppm) may have been too low to produce a detectable effect on hardness. Although SNPs can act as nucleation sites for mineral deposition [22], their impact appears to be dose-dependent. For example, Nozari et al. [23] reported a significant increase in enamel Vickers hardness number (VHN) with a nano-silver fluoride agent containing 376.5 ppm SNPs. The present findings, showing no additional benefit from low-concentration SNPs, are consistent with those of Teixeira et al. [20] and reaffirm the dominant role of fluoride at the tested levels.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. As an in vitro study, the experimental conditions cannot fully replicate the complexity of the oral environment, including salivary flow, pellicle formation, and mechanical abrasion from brushing. The antibacterial assays targeted planktonic bacteria rather than the more resistant biofilm form. The choice of control groups may also limit interpretation: although a commercial comparator (Signal toothpaste) was included, no positive control containing a well-established antimicrobial such as chlorhexidine or triclosan was tested. Furthermore, most products were sourced from a single manufacturer, which may restrict the generalizability of the results to other brands. The relatively small sample size (n = 10 per group) could also reduce statistical power and limit broader applicability.

Future studies should evaluate these formulations in biofilm models that better simulate clinical conditions, explore the effects of higher SNP concentrations on enamel hardness, and confirm these preliminary findings through well-designed in vivo clinical trials to determine the true clinical efficacy and optimal formulation of SNP-based toothpastes.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this in vitro study, the toothpaste containing 20 ppm of silver nanoparticles demonstrated significantly enhanced bactericidal activity against Streptococcus mutans. However, its effect on enamel surface microhardness was comparable to that of the other fluoride-containing toothpastes evaluated.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: H.T., N.P.: Study concept and design; S.S.J., M.T.: Acquisition of data; H.T.: Analysis and interpretation of data; S.S.J.: Drafting of the manuscript; N.P.: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; H.T.: Statistical analysis; H.T.: Administrative, technical, and material support; H.T.: Study supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| SNPs | = Silver Nanoparticles |

| MIC | = Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MBC | = Minimum Bactericidal Concentration |

| VHN | = Vickers Hardness Number |

| S. mutans | = Streptococcus mutans |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This in vitro study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Research Institute of Dental Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Approval No: IR.SBMU.DRC.REC.1401.053).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

As the research involved only anonymized extracted human teeth and no living human participants, the Declaration of Helsinki—which governs research involving human subjects—does not apply to this study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.