All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Clinical Phenotypes of Stage IV Grade C Periodontitis in the Absence of Grade Modifiers: Case Reports

Abstract

Introduction

Stage IV periodontitis grade C, the most severe form of the condition, presents complex clinical and radiographic signs along with rapid progression. One of the key features of this disease is the loss of masticatory function, which requires complex treatments. The phenotype of stage IV periodontitis varies greatly depending on individual patterns. The progression of periodontitis alone can be rapid, even without any grade modifiers such as smoking or diabetes mellitus. This case report aims to present cases of periodontitis IV C with different phenotypes and without grade modifiers. The objective is to analyze variations in the clinical presentation and characteristics of stage IV, grade C periodontitis cases and their treatments.

Case Presentation

This report consists of two cases. The first case is a 34-year-old female patient whose main complaint is that her upper front teeth are mobile and protruding. Intraoral examination showed anterior upper teeth flaring, plaque score (PS) 37%, bleeding on probing (BoP) 36%, and calculus index (CI) 0.54. Periodontal examination showed probing pocket depth (PPD) around 4–11 mm, gingival recession (GR) 1–9 mm, clinical attachment loss up to 13 mm, secondary trauma from occlusion (TFO), tooth mobility degree 1–3, and furcation involvement grade III on 36.

The second case is a 60-year-old female whose chief complaint is missing teeth. Intraoral examination showed gingival redness, anterior deep bite, PS 46%, BoP 86%, and CI 1.2. The PPD was around 2–10 mm, GR 1–5 mm, clinical attachment loss up to 11 mm, tooth mobility degree 1–3, TFO on the anterior, endo-perio lesion, and multiple missing teeth. Both cases were treated following the newest EFP clinical practice guidelines. Both cases were diagnosed with periodontitis stage IV grade C due to their severity and rapid rate of progression. These cases required multidisciplinary approaches.

Conclusion

Proper assessment of periodontitis severity and progression is essential to determine the right treatment plan.

1. INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is a multifactorial inflammatory disease that affects the tooth-supporting tissues and is caused by specific microorganisms. Following advances in scientific knowledge, the accumulation of basic science evidence, and the evaluation of predisposing risk factors—including genetic predisposition, systemic conditions, and hormonal influences—the classification of periodontal diseases has undergone repeated modifications [1, 2]. Based on our experiences with the previous classification, distinguishing between chronic and aggressive periodontitis often posed significant challenges, largely due to the limited availability of longitudinal data on disease progression. Periodontitis with rapid bone destruction often results in early tooth loss and leads to significant impairment of masticatory function in the future. Aggressive periodontitis was previously associated with periodontal tissue destruction that was inconsistent with the amount of bacterial deposits present, particularly in otherwise healthy individuals with a family history of rapid periodontitis [1, 2].

Since its introduction in 2018, the periodontitis classification based on the staging and grading framework has become more practical. Staging is a system adapted from oncology that allows an integrated diagnostic classification to determine the current state of periodontitis [3]. Staging (stage I–IV) is determined by disease severity after considering several clinical and radiographic findings, including clinical attachment loss, the amount and percentage of bone loss, probing depth, the presence and extent of angular bony defects and furcation involvement, tooth mobility, and tooth loss due to periodontitis. Meanwhile, the grading system represents the observed or inferred rate of progression and the risk of further destruction due to environmental exposures and systemic comorbidities. Grades of periodontitis are divided into three categories (A: slow; B: moderate; and C: fast) [3]. Certain risk factors, such as smoking and diabetes mellitus, can independently increase the grade score regardless of the primary criterion; these factors are known as grade modifiers [3].

The designation of stage IV, grade C periodontitis offers a more clinically applicable framework, effectively bridging the gap between the former categories. The world consensus on the new classification has also recognized four major case types of stage IV periodontitis. In addition, risk factors such as smoking and diabetes status can modify the grade of periodontitis, although the rapid progression characteristic of grade C is not always associated with these factors. The phenotypes of stage IV periodontitis involve functional and esthetic considerations that vary considerably depending on individual clinical patterns [4]. To facilitate clinical decision-making, treatment guidelines have been developed based on the four major case types of stage IV periodontitis. Accordingly, the aim of this case report is to analyze variations in the clinical presentation and treatment approaches in patients with stage IV, grade C periodontitis.

2. CASE REPORT

Both patients came to the Dental Hospital, Faculty of Dentistry, Universitas Indonesia. The patients signed informed consent forms for a complete periodontal examination and for the use of their data for academic purposes.

2.1. Case 1

A 34-year-old female patient was referred by an orthodontist to our Periodontology Department. The patient came for a consultation with the main complaint of protruding anterior teeth and increasing mobility of several teeth, which she described as becoming more pronounced over time. Several years prior, the patient lost a tooth due to severe mobility. She reported no systemic conditions, including diabetes mellitus (HbA1C level 5.2), and no history of smoking. However, the patient reported a familial tendency toward tooth loss. She brushes her teeth 2–3 times daily; however, her last dental scaling appointment was three years ago.

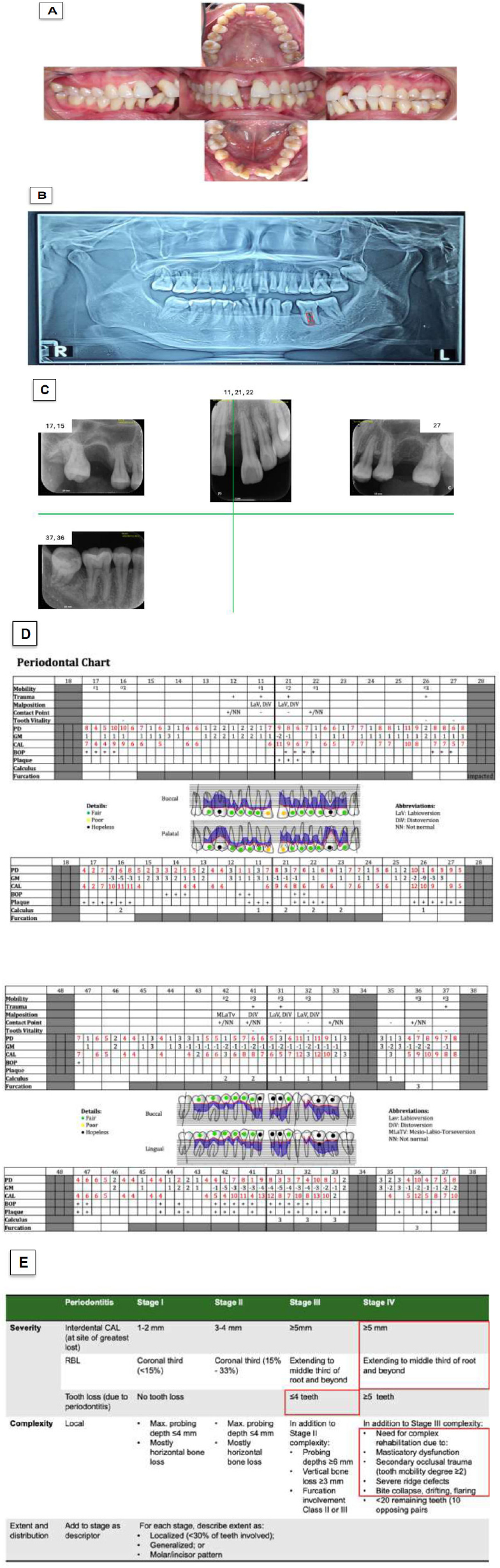

The clinical examination revealed a plaque score of 37% and bleeding on probing (BoP) of 36%, indicating active periodontal inflammation. The patient exhibited flaring of the anterior maxillary and mandibular teeth, accompanied by central diastemas in both arches. Teeth 16, 26, 31, 32, 41, 42, 36, and 37 demonstrated second- to third-degree tooth mobility (Fig. 1A-E). Tooth 34 was missing, and class II furcation involvement was present on tooth 36. The clinical attachment loss (CAL) ranged from 2 to 13 mm (Fig. 1A and D). The radiographic bone loss extended from the mid-third to the apical-third of the root, with vertical bone loss reaching the mid-third of the root of tooth 47. In addition, teeth 16, 26, and 36 showed radiolucency in their apical regions (Fig. 1B and C).

The severity factor for staging this case was determined by the greatest loss of interdental CAL and radiographic bone loss. This case was classified as stage IV due to the greatest interdental CAL of 13 mm at tooth 32 and radiographic bone loss reaching the mid-third of the root and beyond. Additionally, based on the complexity factors, this case exhibits nearly all indicators of the need for complex rehabilitation, such as flaring, drifting, masticatory dysfunction, and secondary occlusal trauma. Regarding the extent of the disease, the data suggested a likely molar-incisor pattern, as these teeth were the most severely affected. The pathological tooth migration in this case required correction through orthodontic treatment. Therefore, this case is classified as type 2 of stage IV periodontitis (Fig. 1E).

The grading of this case was primarily determined by the 100% bone loss of tooth 36 divided by the patient’s age (34 years), resulting in a ratio of 2.9. This score indicates rapid progression of periodontal destruction. However, this case did not have any grade modifiers because the patient’s HbA1C level was normal and the patient was a nonsmoker. The final diagnosis for this case is molar-incisor stage IV, grade C, type 2 periodontitis.

Case 1 clinical presentation and classification decision-making. (A) Intraoral conditions. (B) Panoramic radiograph. (C) Periapical radiographs taken after initial treatment. (D) Full-mouth periodontal chart. (E) Staging and grading criteria as established in the 2017 World Workshop.

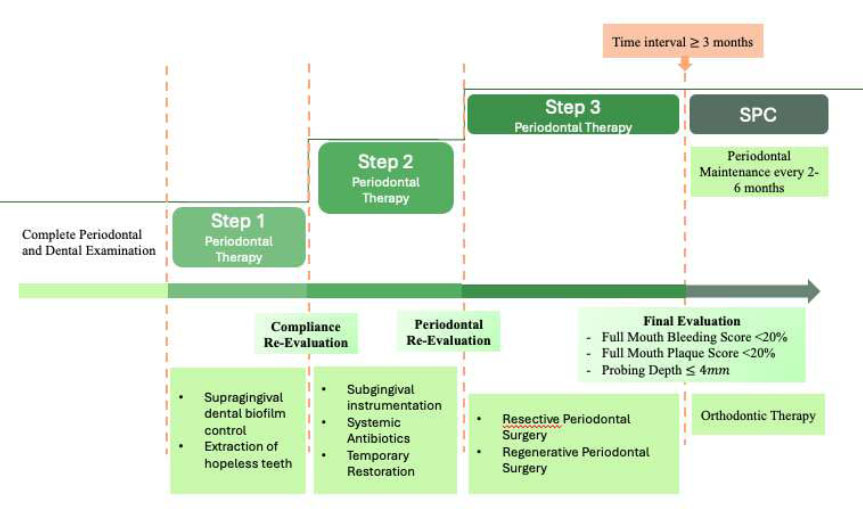

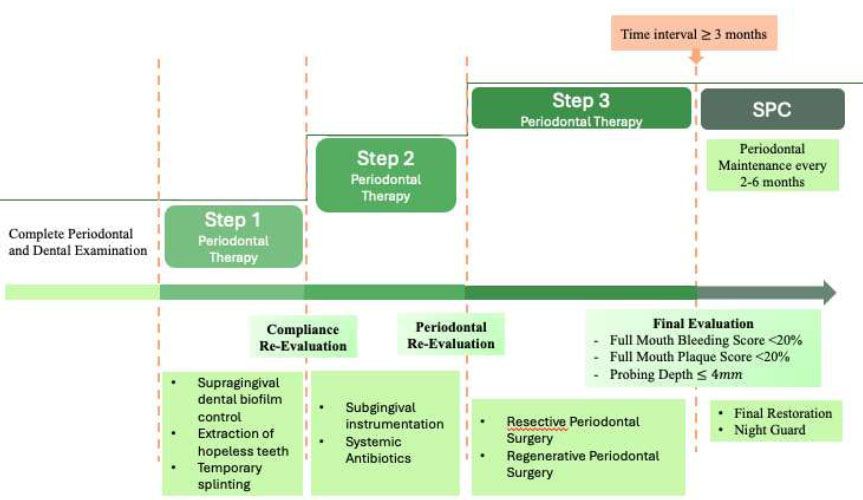

Following the initial examination, treatment was initiated with intensive patient education to improve oral hygiene and control risk factors, including the extraction of hopeless teeth. After re-evaluating the patient’s compliance, therapy proceeded with subgingival instrumentation supplemented by adjunctive systemic antibiotics. A temporary removable partial denture was fabricated to replace the missing mandibular anterior teeth. Periodontal surgery was indicated for sites that did not respond adequately to non-surgical therapy or that exhibited residual probing depths ≥ 6 mm. Periodontal maintenance visits were scheduled every 2–6 months to ensure long-term stability. Subsequently, orthodontic therapy was initiated after achieving periodontal stability, defined by a full-mouth bleeding score < 20%, a full-mouth plaque score < 20%, and probing depths ≤ 4 mm (Fig. 2).

2.2. Case 2

A 59-year-old female patient came to our dental hospital for a consultation. Her main complaint was tooth mobility, which eventually resulted in tooth loss. The patient sought a denture to replace the missing teeth. Her last dental appointment was for a tooth filling five years prior, and she had not undergone any scaling treatment until her visit to our hospital. The patient reported brushing her teeth three times a day with a soft toothbrush. She denied having systemic diseases or any familial genetic conditions associated with tooth loss. She was a nonsmoker but reported a habit of bruxism.

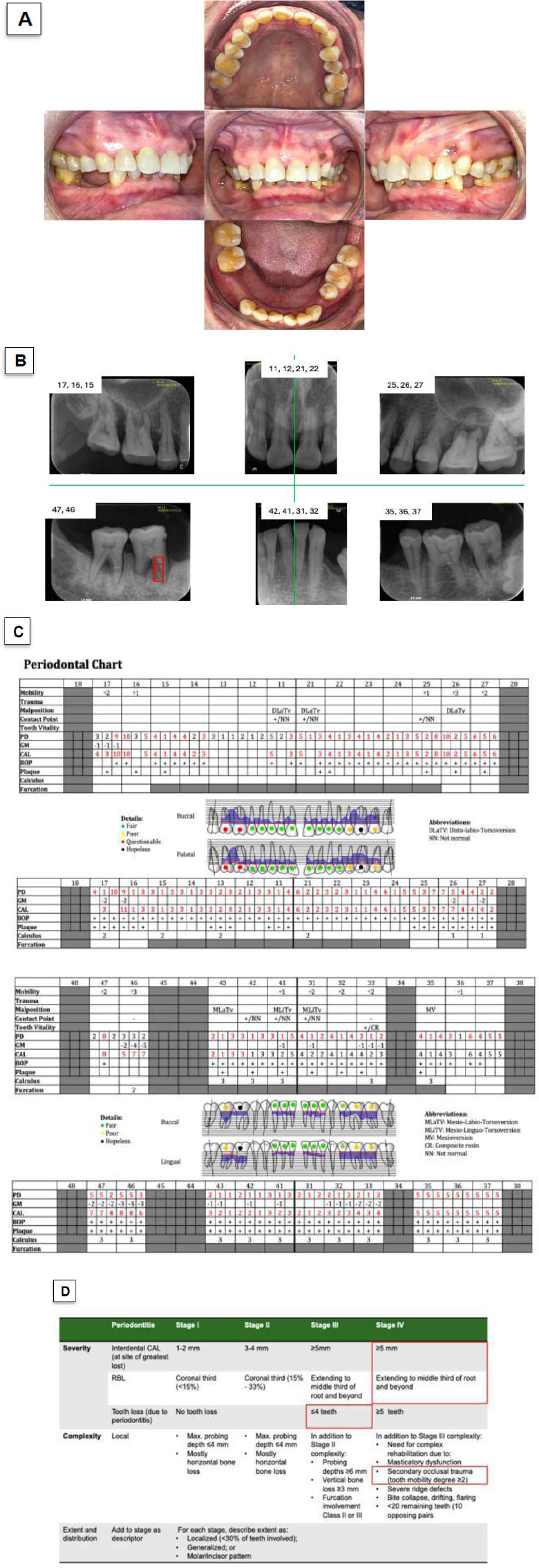

The clinical findings showed a plaque score of 46% and a BoP score of 86%, with generalized gingival erythema. Clinical attachment loss (CAL) varied considerably, measuring between 2 and 10 mm, reflecting moderate to advanced periodontal destruction (Fig. 3A-D). Probing depths ranged from 1 to 10 mm, with deeper pockets located in the posterior maxilla. Multiple teeth exhibited mobility, with grade 3 mobility in teeth 26 and 46; grade 2 mobility in teeth 17, 27, 47, 31, 32, 33, and 37; and grade 1 mobility in teeth 16, 25, 36, and 41. Tooth 26 exhibited class II furcation involvement (Fig. 3A and C). The periapical x-ray showed radiographic bone loss ranging from the cervical-third to the apical-third of the root, along with a noticeable increase in radiolucency in the furcation areas of teeth 46, 47, and 37 (Fig. 3B).

The case could qualify for stage III or stage IV based on the clinical severity component alone. However, based on the complexity component, the presence of secondary occlusal trauma on several teeth determined that this case should be classified as stage IV periodontitis. Since approximately 56% of the teeth had a CAL of ≥ 5 mm, this case is classified as generalized periodontitis. Without full-arch rehabilitation to replace the missing teeth, this case is categorized as type 3 in stage IV periodontitis (Fig. 3D).

Regarding disease progression, the radiographic bone loss-to-age ratio (100% / 59 = 1.69) classified this case as grade C. Despite the absence of systemic risk factors and smoking, the risk of periodontal disease progression remains significant and increases at a rapid rate. The final diagnosis for this case is generalized stage IV, grade C, type 3 periodontitis.

The implemented periodontal therapy followed the structured protocol outlined above (Fig. 4). The initial phase (Step 1) involved the extraction of hopeless teeth and the stabilization of teeth with second degree mobility using temporary splinting. Following confirmation of patient compliance, Step 2 therapy was performed, consisting of subgingival instrumentation supplemented with systemic antibiotics. Residual pockets (≥6 mm) identified during periodontal re-evaluation were addressed with periodontal surgery. The patient was then placed on a supportive periodontal care regimen with maintenance visits every 2-6 months to preserve periodontal health. The final phase involved the placement of definitive restorations to replace missing teeth and a night guard to manage the patient's bruxism.

3. DISCUSSION

The classification system in dentistry is used to transform clinical data into a diagnosis to assist treatment planning and to estimate both short- and long-term prognosis customized for each patient [5]. Based on important differentiating features such as attachment loss, bone loss, and tooth loss due to periodontal disease, clinicians can determine the severity of periodontitis [3, 6]. In both the first and second cases, a significant amount of CAL (≥ 5 mm) in interdental areas, grade 2–3 mobility, tooth loss, and severe radiographic bone loss were observed. Both cases were diagnosed with periodontitis stage IV grade C due to their severity and rapid rate of progression.

Treatment flow of case 1.

Case 2. Clinical presentation and classification decision-making. (A) Intraoral conditions. (B) Periapical radiographs taken before initial treatment. (C) Full-mouth periodontal chart. (D) Staging and grading criteria as established in the 2017 World Workshop.

Treatment flow of case 2.

There is a notable difference between the two cases. In case 1, despite the more distinct appearance of severe periodontal breakdown, the plaque score and BoP were lower than in case 2. Based on the medical history of the patient in case 1, she had a family history of similar periodontal problems. Genetic and epigenetic factors are known to be major risk factors for periodontitis. Dysbiosis can occur when the host responds pathologically to the accumulation of normal resident biofilm. The aberrant host response is most often characterized by hyperfunctionality of polymorphonuclear neutrophils, leading to increased release of tissue-destructive enzymes, reactive oxygen species, lysozyme, collagenases, elastase, inflammatory cytokines, and chemokines. Neutrophils also play an important role in recruiting Th17 cells, which promote osteoclast activity [7]. In this case report, both patients were adult females. Numerous hormones, including steroids and estrogens, are known to influence the progression of periodontitis through their regulatory effects on bone formation and resorption [8].

A review of multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses identified several polymorphisms in interleukins and other cellular and inflammatory mediators [9]. Case 1 also showed pathological tooth migration in the form of anterior flaring, which clearly supports its classification as stage IV. Posterior bite collapse, mesial drifting, and flaring of the incisors have been characterized as specific phenotypes of stage IV periodontitis [10, 11]. Although only one tooth was missing, the secondary malocclusion resulting from pathological tooth migration caused masticatory dysfunction that required complex rehabilitation [3, 6].

Meanwhile, if we consider only the severity of clinical signs in case 2, the disease could be classified as either stage III or stage IV. However, considering the local factors such as high plaque score and BoP that increased disease complexity, signs of secondary trauma from occlusion were found in the lower anterior mandible in case 2. A finite element analysis study demonstrated that stress concentrations increase at the apex when bone height is reduced. The force distribution relative to surface area becomes intensified due to the loss of supporting tissues, resulting in a decreased contact surface [12]. Case 2 also presented slight mesial drifting in the mandibular molar region, which can contribute to further deterioration of the dentition [10]. The involvement of endo-perio lesions was also detected on teeth 16 and 26.

The most reliable indicator of disease progression is the longitudinal evaluation of radiographic bone loss (RBL) or clinical attachment loss (CAL). In cases of stage III and IV periodontitis, grading is often determined indirectly by assessing the rate of bone loss relative to the patient’s age. A bone loss-to-age ratio greater than 1.0 typically classifies the patient as grade C, indicating rapid progression [3]. Neither case included smoking habits or diabetes mellitus as risk factors for further progression. However, both cases demonstrated high severity and rapid disease progression.

The progression of periodontitis is influenced by multiple factors that modulate the host response to microbial challenge [6]. Grading is dynamic and may change over time, either upward or downward, based on the clinician’s judgment following a comprehensive assessment of risk factors. This is because grading is not determined by pathological levels of specific biological biomarkers [6, 13]. Although several salivary biomarkers have been identified in periodontitis, their clinical applicability requires further research to validate their usefulness as objective measures for grading [14, 15].

CONCLUSION

Patients diagnosed with Stage IV periodontitis typically exhibit rapidly progressive damage to the periodontal attachment. Because staging is based on individual patient assessment, Stage IV can vary in its phenotypic appearance depending on the specific patterns of periodontal breakdown. These phenotypic variations may arise from genetic and epigenetic influences, as well as patient-related, site-specific, and anatomical risk factors. Early and accurate diagnosis, followed by timely multidisciplinary treatment, is essential to prevent further tooth loss and occlusal impairment.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: N.A.H. and Y.S.: were responsible for study conception and design; F.A.D.: Handled data collection; N.A.H. and F.A.D.: Contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results; and N.A.H. and F.M.T.: Prepared the draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All the data and supporting information are provided within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This APC is funded by the Faculty of Dentistry, Universitas Indonesia.