All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Single-stage Correction of Unilateral TMJ Ankylosis and Associated Micrognathia: A Case Report

Abstract

Introduction

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) ankylosis is a debilitating condition that can lead to severe functional limitation and dentofacial deformities. We report a case of a young adult male with unilateral left bony TMJ ankylosis, presenting with a Class II Division 1 malocclusion on a Class II skeletal base, marked mandibular retrognathia (micrognathia) with chin deficiency, and facial asymmetry.

Case Presentation

A 16-year-old male presented with a 10-year history of restricted mouth opening following trauma (fall from a bicycle). Clinical and radiographic evaluation revealed left-sided bony TMJ ankylosis with associated facial asymmetry, chin deviation, and micrognathia. Mouth opening was limited to 4 mm. The patient underwent interpositional gap arthroplasty with temporalis muscle graft and advancement genioplasty in a single operative session. Postoperatively, there was gradual and sustained improvement, with mouth opening reaching 40 mm at 1-year follow-up. The surgical site remained healthy, and significant aesthetic enhancement was achieved.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates that single-stage surgical correction of TMJ ankylosis and associated facial deformities, such as micrognathia, is not only feasible but also effective in improving both function and facial harmony. Early surgical intervention using a combined approach can prevent long-term complications such as obstructive sleep apnea, speech disturbances, and psychological distress, making it a valuable strategy in managing pediatric and adolescent TMJ ankylosis.

1. INTRODUCTION

TMJ ankylosis is an uncommon but severe condition characterized by fusion of the mandibular condyle to the cranial base, resulting in limited jaw mobility. The condition most often arises from trauma or infection (such as childhood injury or septic arthritis) and can also be associated with diseases like rheumatoid arthritis [1]. The overall prevalence is low; for example, a survey in an endemic region reported TMJ ankylosis in approximately 0.46 per 1,000 children (0.046%) [2]. Clinically, patients typically presented with a chronic, painless restriction of mouth opening and difficulty in mastication and speech [3].

In growing patients, ankylosis can arrest condylar growth, leading to facial asymmetry and mandibular micrognathia [4]. Characteristic findings included a deviation of the chin toward the affected side, a “bird-face” appearance due to mandibular retrusion, and dental malocclusion (often Class II with an increased overjet) [5]. In severe cases, the retruded mandible and altered airway dimensions might precipitate Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), further compounding the health impact [6]. Optimal management of TMJ ankylosis aimed to restore mandibular function (improve mouth opening), correct facial deformities, and prevent re-ankylosis [7].

Surgical treatment was required and classically involved gap arthroplasty (resection of the bony or fibrous ankylotic mass), often combined with interpositional grafts (such as temporalis muscle/fascia, dermis-fat, or alloplastic materials) to maintain a gap and discourage refusion [8]. In growing patients or extensive deformities, additional procedures like condylar reconstruction with costochondral grafts or distraction osteogenesis might be considered to restore mandibular height and allow for normal growth.

Adults with long-standing ankylosis frequently require orthognathic surgical measures to address the resultant jaw deformity (e.g., retrognathia or open bite) once the joint is released. Traditionally, a staged approach had been used, first performing the TMJ release followed by orthognathic correction in a separate surgery after a period of physiotherapy. However, a single-stage approach combining TMJ ankylosis release and simultaneous orthognathic surgery has been explored to reduce total treatment time and to immediately address both functional and aesthetic issues [9].

Recent advancements in digital technology, such as high-resolution 3D imaging, computer-assisted virtual surgical planning, patient-specific implant design, and 3D printing of surgical guides, have further enhanced the precision and predictability of managing complex TMJ ankylosis cases [10]. These tools allowed surgeons to simulate the joint release and jaw repositioning preoperatively and even fabricate custom TMJ prostheses or cutting guides for use during surgery [10]. Such digital integration could improve surgical outcomes and reduce intraoperative guesswork in complex reconstructions.

In this report, we presented a case of unilateral TMJ bony ankylosis in an adult with severe mandibular deficiency and malocclusion, managed successfully with a single-stage surgical correction. We described the clinical presentation, the combined surgical technique employed, and discussed the outcome in light of current literature on similar cases. This case underlined the potential of single-stage corrective surgery for TMJ ankylosis with coexisting dentofacial deformities, as well as the considerations necessary to ensure a favorable result.

2. CASE REPORT

A 16-year-old male patient reported to the Outpatient Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Siddharth Gupta Memorial Cancer Hospital at Sawangi, Wardha with a chief complain of reduced mouth opening for 10 years. The patient reported a history of a Road traffic accident due to a slip and fall from a bicycle 10 years ago. Patient went to a private hospital at Amravati, Maharashtra, where a CT scan of the Face was conducted, reports suggestive of “Medially displaced condylar fracture of left side”, and the Patient was managed through a Conservative approach of IMF for 4-5 weeks (Fig. 1A-D).

Preop photos.

A. Frontal view B. Lateral view (left side) C. Mouth opening D. Midline.

There was no positive congenital and prenatal history, including history of consumption of teratogenic medications, any invasive procedure/ sex determination during pregnancy, forceps delivery, or premature birth. Patient gave history of a habit of snoring during sleep for approximately 8-10 years and difficulty in speech for 10 years.

On local examination, the patient’s face was asymmetrical, with the chin deviating towards the left side. Flatness was seen on the right side of the face, and fullness was seen on the left side of the face. The mandible was retrognathic. The facial profile was convex. On TMJ examination, there was reduced mouth opening with restriction of lateral excursive jaw movements. Lips were potentially competent. Loss of the mental labial sulcus was seen. On Ear examination, no active infection or discharge was seen.

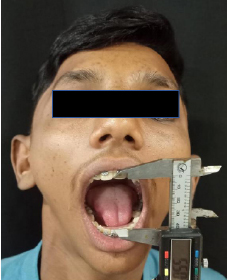

On intraoral examination, the Patient's mouth opening was approximately 4 mm. All sets of permanent teeth were present except for third molars. There was a protrusion of upper and lower anterior teeth. Occlusion was bilaterally stable with a class II molar relation. The midline of the central incisors was also shifted towards the left side.

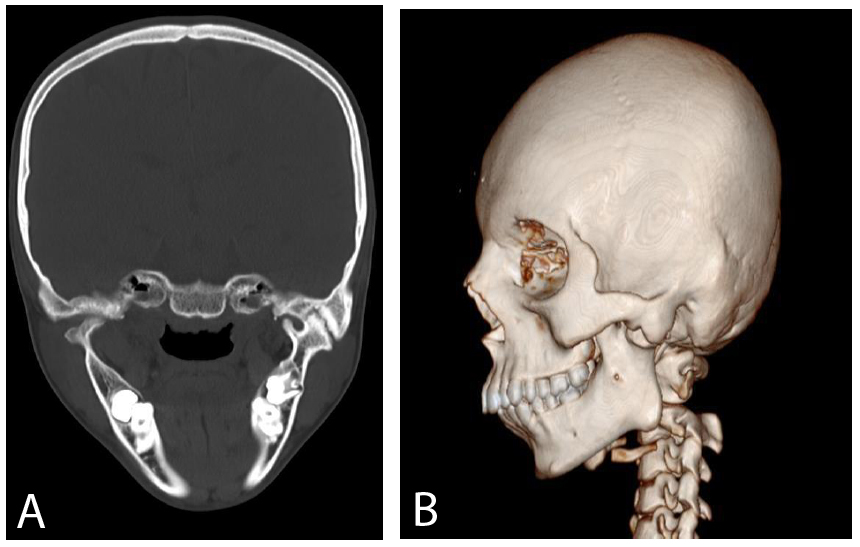

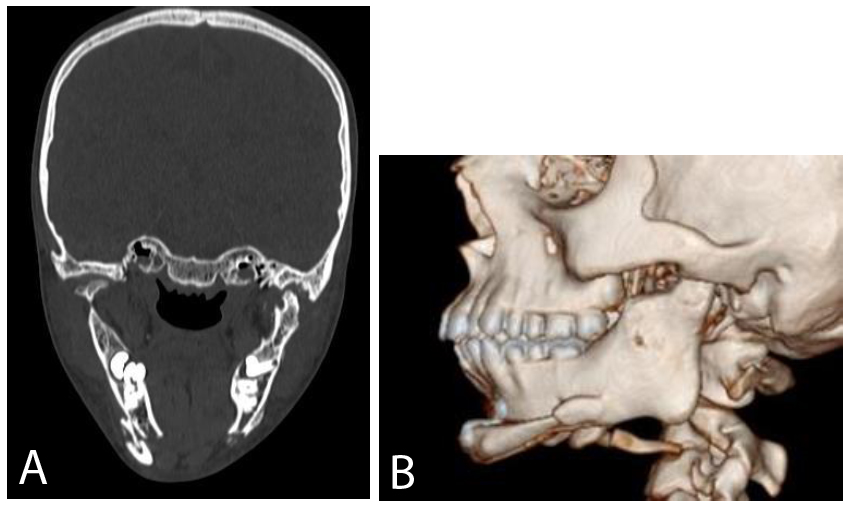

The provisional diagnosis for this was Traumatic TMJ Ankylosis of the left side. To confirm the same, CT Face was conducted with 3D reconstruction in all Coronal, axial, and sagittal sections of 1.5 mm slices. Reports were suggestive of Bony ankylosis of the TMJ of the left side (Fig. 2A-B).

CT scan (showing TM joint ankylosis over the left side).

A. Coronal VIEW B. 3DCT.

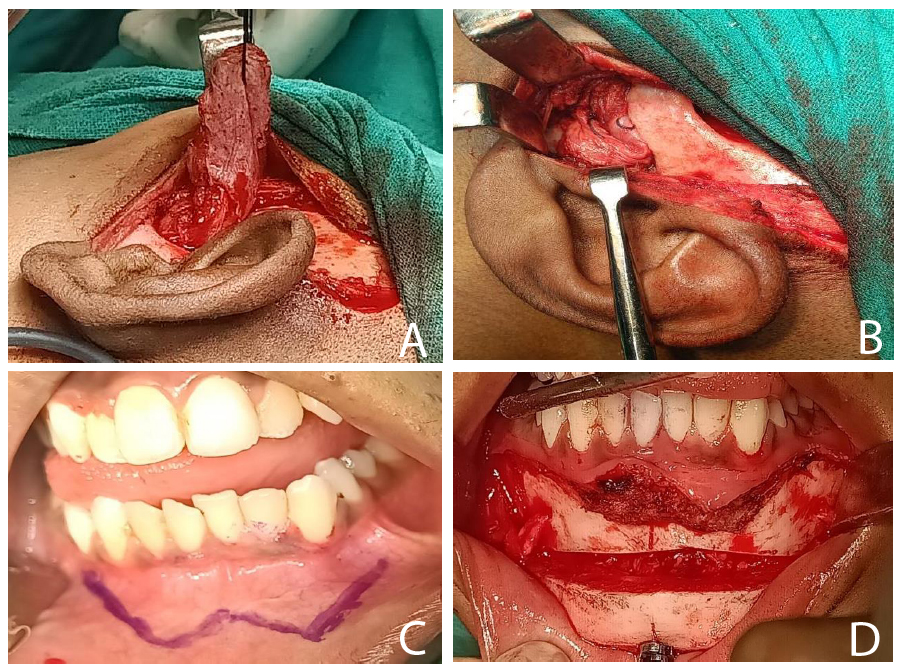

The patient was then planned for surgical intervention under general anesthesia, followed by nasoendotracheal intubation. After preparing and draping the patient, standard marking was done for the left preauricular incision. Exposure of the bony ankylotic TMJ mass on the left side was followed by its release. Interpositional gap arthroplasty was performed on the left side using a temporalis muscle graft (Fig. 3A-D).

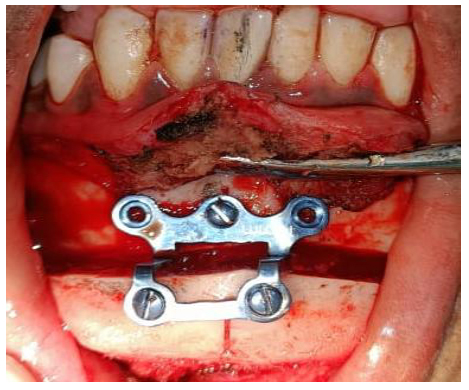

Markings for Advancement genioplasty were given over the lower labial mucosa. Advancement genioplasty with symmetry correction was performed to coincide with the dental and skeletal midline. A genioplasty plate of size 2 mm with five screws (2 mm × 10 mm each) was placed. A Romovac drain was placed over the left preauricular region. Closure was done in layers. Intraorally, the muscle and mucosa were sutured with 3-0 Vicryl, and extraorally, the muscle layer was sutured with 3-0 Vicryl and the skin layer with 4-0 Ethilon. Pressure dressing was given over the preauricular and chin region. The patient was advised to perform active mouth opening exercises postoperatively using a Hister jaw opener. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 10 with a mouth opening of approximately 18 mm (Figs. 4A-D and 5, respectively).

A. preauricular incision, B., C. Exposure of left TM joint, D. Part of condyle removed.

A. Harvesting of temporalis fascia, B. interpositional arthroplasty with temporalis fascia, C. Incision marking for genioplasty D. Osteotomy cuts for genioplasty.

The patient was recalled for regular follow-up visits, during which the mouth opening gradually increased, and the surgical site was found to be healthy with no signs of dehiscence, gapping, collection, or discharge (Fig. 6A-B).

Advancement genioplasty and plating.

CT scans A. Coronal view, B. 3DCT.

The patient’s facial profile also improved, and mouth opening gradually increased to 40 mm at the 1-year follow-up visit (Figs. 7A-B and 8, respectively).

Post OP photos A. Frontal view, B. Lateral view (left side).

Post operative mouth opening (40 MM).

3. DISCUSSION

The term “ankylosis” is derived from Greek and refers to a stiff joint. It essentially denotes stiffening (immobility) or pathological intracapsular fusion/union, which may occur either via fibrous tissue adhesion or bony deposition, between the head of the condyle and the articular surface of the glenoid fossa. The resulting immobility of the joint adversely affects jaw function, leading to hypomobility or complete immobility. This manifests clinically as an inability to open the mouth, ranging from partial to complete restriction, which can interfere with mandibular development in growing children, resulting in malocclusion, facial deformities, and obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome.

The exact incidence of intra-articular TMJ ankylosis is challenging to determine. However, in Western literature, its reported incidence has declined, attributed to improved management of condylar fractures and decreased rates of middle ear infections following the widespread use of antibiotics. Conversely, in India, the incidence remains high. The reported age distribution ranges from 2 years to 63 years, with onset typically occurring before the age of 10.

TMJ ankylosis can present in various forms, including false or true ankyloses, extra-articular or intra-articular, fibrous or bony, unilateral or bilateral, and partial or complete ankylosis.

The definitive etiology of TMJ ankylosis remains unclear, although two main predisposing factors are recognized: trauma and infection in or around the joint region. In 1968, Topazian reported that 26% to 75% of TMJ ankylosis cases were attributable to trauma, while 44% to 68% resulted from infection. Trauma remains the leading cause, with others including rheumatoid arthritis, degenerative arthritis, infectious spondylitis, and psoriasis [14]. According to existing literature, trauma accounts for 75% to 98% of TMJ ankylosis cases [2-6].

The degree of facial deformity depends on the type of ankylosis, as well as its onset and duration. During the growth phase, deformities can be severe, impacting nutrition, speech, growth, oral hygiene, dental eruption, malocclusion, and, when micrognathia occurs, obstructive sleep apnea. Post-growth, ankylosis primarily leads to functional impairment, with minimal aesthetic deformity. The most severe form of ankylosis arises from an intracapsular condylar fracture, which can more extensively affect the surrounding soft tissues in addition to the condylar head [1].

Marked facial asymmetry and restricted mouth opening can result in numerous functional impairments, including difficulty chewing food and maintaining oral hygiene, which may ultimately contribute to psychosocial disability [7-10]. TMJ ankylosis may also lead to a severe Class II malocclusion characterized by an anterior open bite and posterior crossbite [7].

The management of TMJ ankylosis is inherently surgical. Early surgical correction is recommended to achieve satisfactory joint function. The choice of surgical strategy is guided by factors such as age of onset, extent of ankylosis, unilateral or bilateral involvement, and the presence of associated facial deformities.

Different surgeons have advocated various surgical techniques. However, critical evaluation has identified three principal approaches: condylectomy, gap arthroplasty, and interpositional arthroplasty. Less commonly employed methods include total joint replacement and distraction osteogenesis [11, 12].

An internationally accepted sequential protocol for the management of TMJ ankylosis was proposed by Kaban, Perrott, and Fisher in 1990. This protocol includes early surgical intervention, aggressive resection to create a gap of at least 1 to 1.5 cm, ipsilateral coronoidectomy and temporalis myotomy, contralateral coronoidectomy and temporalis myotomy, lining of the glenoid fossa with temporalis fascia, reconstruction of the ramus using a costochondral graft, early mobilization and intensive physiotherapy for at least six months postoperatively, regular long-term follow-up, and if required, cosmetic surgery after completion of facial growth [11]. In the present case report, interpositional gap arthroplasty was performed using a temporalis muscle graft to avoid complications associated with foreign body grafts. Additionally, advancement genioplasty was carried out to correct the associated micrognathia.

TMJ ankylosis with micrognathia is a very challenging condition based on the effect on facial symmetry, patency of the airway, and masticatory function [13-15]. OSA complicates the surgery further, requiring a multidimensional approach to treat functional and esthetic problems concurrently [14]. The compromise of the upper airway in these patients has been well established, emphasizing the vital correlation between mandibular position and pharyngeal airway dynamics [14].

Single-stage surgical correction has been employed as a valuable alternative in the effective treatment of such complicated problems [15]. Anchlia et al. also provided recommendations emphasizing the conjunction of TMJ release, mandibular advancement, and, if necessary, genioplasty, to achieve a maximum of function and facial harmony [15]. Their method emphasizes addressing OSA risk in the surgical plan because sleep-disordered breathing can significantly affect postoperative outcomes [15].

The systematic review by Yew et al. emphasized the surgical management of the triad of micrognathia, TMJ ankylosis, and OSA, highlighting consistent variations in surgical techniques but uniform support for individualized, multidisciplinary planning [16]. Individualized treatment reduces complications and enhances long-term function and aesthetics [16].

Treatment of unilateral TMJ ankylosis with associated micrognathia also needs to take into consideration the possibility of bilateral involvement or compensatory growth deformity [17]. Nariai et al. reported on the surgical and prosthetic rehabilitation of bilateral TMJ ankylosis, highlighting the adaptability of distraction osteogenesis and prosthetic rehabilitation for complicated cases [17]. Theirs was a bilateral case, but their concepts of synchronized prosthetic and surgical rehabilitation can be just as well applied to unilateral cases, specifically in achieving harmonious occlusion and stable joint function [17]. Mandibular distraction osteogenesis has also been used with increased frequency as an adjunct or alternative to conventional osteotomies for mandibular advancement in patients with micrognathia and TMJ ankylosis [18]. Yu et al. proved the long-term success of this procedure in children with substantial airway gain and gains in facial symmetry [18]. It has to be noted, however, that secondary TMJ ankylosis following distraction osteogenesis is a complication reported by Schlund et al. [19]. This emphasizes the utility of careful surgical technique and postoperative physiotherapy in order to preserve joint mobility and avoid re-ankylosis [19].

TMJ ankylosis classification systems, as proposed by Upadya et al., are useful in planning surgery by grading ankylosis severity and morphology [20]. Their grading helps in the choice of gap arthroplasty, interpositional arthroplasty, or joint reconstruction based on the degree of joint involvement and the presence of any accompanying deformity [20]. These systems are extremely useful in planning single-stage corrections, where optimal functional and aesthetic results require a comprehensive approach to the pathology [20].

The complex issues noted in instances of TMJ ankylosis, particularly when combined with developmental deformities like condylar aplasia, highlight the value of deliberate preoperative planning and interprofessional collaboration [21]. Vagha et al. illustrated this in managing a child patient, noting the surgical intricacies and postoperative complications essential for achieving optimal outcomes [21]. Their findings also highlight the value of meticulous assessment and individually oriented treatment plans, especially in attempts at achieving single-stage correction of TMJ ankylosis and micrognathia [21].

In the present case, a cephalometric evaluation revealed significant skeletal discrepancy typical of a Class II skeletal malocclusion. The ANB angle measurement was 6.9°, which reflects a significant maxillomandibular discrepancy. This was just above the average ANB of 6.64° (95% CI, 6.15°–7.13°) of the Class II surgical cases in a recent cephalometric study, thus establishing the severity of the skeletal relationship and justifying the need for orthognathic surgical correction [22]. The SNA angle was 82.1°, reflecting that the maxilla was in normal position, while the SNB angle of 75.2° reflected severe mandibular retrusion. An analysis by the McNamara method revealed a short mandibular length of 102 mm and a maxilla length of 52 mm, resulting in a maxillomandibular differential of 50 mm, which is far below normative expectations. Additionally, an analysis of the jaw position in relation to the true vertical line of the Nasion revealed a +3 mm projection of Point A (maxilla) and a –10 mm retrusion of Pogonion (mandible), further supporting the skeletal imbalance controlling the sagittal and vertical planes. These skeletal findings, coupled with the patient's obstructive sleep apnea and facial asymmetry, graded the case as IOFTN Grade 5. This reflected an urgent need for surgical correction due to functional and aesthetic concerns, as justified by recent clinical validation studies related to the IOFTN scoring system in complex craniofacial cases [23]. Thus, the decision to perform a one-stage TMJ ankylosis release with advancement genioplasty was made after considering cephalometric, functional, and orthodontic factors rationally.

4. LIMITATIONS

This report has several limitations. First, a comprehensive cephalometric analysis of the pre- and post-operative changes was not fully documented, only select measurements (such as ANB) were reported, which limits the quantitative assessment of skeletal changes. Second, aside from the sleep study for OSA, we lacked other objective functional outcome measures (for example, metrics of masticatory efficiency or jaw muscle strength) to quantify the improvement in function. Third, the patient’s psychosocial outcomes were not formally evaluated – while he subjectively reported satisfaction, no standardized quality-of-life questionnaires were administered to measure the psychosocial impact of the treatment. Additionally, the follow-up duration (in this case, 6 months) was relatively short. A longer follow-up is necessary to ensure stability of the results and to monitor for potential recurrence of ankylosis or other late complications. These limitations highlight the need for further studies and long-term case tracking to better establish the outcomes of single-stage TMJ ankylosis corrections.

CONCLUSION

Unilateral TMJ ankylosis with associated micrognathia and malocclusion is a complex condition requiring a carefully coordinated treatment strategy. This case report demonstrates that a single-stage surgical approach, combining TMJ ankylosis release, immediate mandibular repositioning, and adjunctive procedures like genioplasty, is feasible and can achieve gratifying improvements in jaw function, occlusion, facial symmetry, and even airway patency in a single operative session. The successful outcome in our patient underscores the potential benefits of an integrated approach, especially when supported by thorough planning and modern digital aids. However, it is important to recognize that this is a technically demanding solution that may not be universally applicable. Patient selection, surgeon experience, and available resources (such as virtual planning technology) all influence the suitability of a single-stage correction. Caution and individualized judgment should guide its use. In summary, single-stage correction offers a promising option for comprehensive management of TMJ ankylosis with concomitant deformities, meriting consideration in severe cases. Ongoing follow-up and further reports will help validate the long-term stability of this approach and determine its role in the broader context of TMJ ankylosis management.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: N.B. and S.K.: Contributed to the study conception and design; S.K.:Data collection was performed; N.B. and S.K.: Analysis and interpretation of results were conducted; N.B. and S.K.: The draft manuscript was prepared. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical approval for this clinical case report was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences (DMIMS), Wardha, India. Approval Number: DMIMS(DU)/IEC/2024/845.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors extend their gratitude to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery for providing clinical support. No financial or material support was received for this study.