All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Knowledge and Experience of Saudi Dental Practitioners with Intraoral Scanners

Abstract

Background

Teeth are digitalized using intraoral scanners, which is an efficient way to get a patient-provided direct digital model. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the experience of Saudi dental practitioners with intraoral scanners, investigate the current knowledge and improve the practice accordingly.

Methods

Electronic questionnaires were randomly sent to Saudi dental professionals. Of the 400 questionnaires that were submitted for the study, 310 were determined to be reliable. Details on the practitioners' gender, experience level, and practice level were documented. The capabilities and advantages of intraoral scanners, which require IOS knowledge and training, and understanding of how to use IOS were also recorded. The gathered data was examined using descriptive statistics, which includes numbers and percentages. The findings were analyzed using the Chi-square and Fisher's Exact tests.

Results

There were 161 women (51.8%) and 149 men among the participants (47.9%). General practitioners (198, or 63.7%) had the most subjects, followed by specialists in restorative (80, or 25.7%) and consultants (32, or 10.3%). In terms of IOS use in dental practice, most participants (70.6%) do not use it, while less than one-third do. The majority of participants (52.3%) intend to purchase IOS with significant variations based on gender, experience, and level of practice (p<0.05). Compared to traditional, most participants believe that IOS will eventually replace it, improve quality, and be more aesthetically pleasing. Most dentists believe that using IOS requires special skills and training. More than half of dentists believe IOSs have the same level of accuracy as conventional in producing three units FPDs, implant prosthesis, and complete denture.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that dentists have a high level of satisfaction and a favorable attitude toward using IOS technology in clinical dentistry practice.

1. INTRODUCTION

The field of dentistry has seen rapid advancements in digital technology, particularly with the advent of computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) systems [1]. The CAD/CAM system utilizes an intraoral scanner (IOS) for the purpose of obtaining digital impressions [2]. In order to digitize dental structures, intraoral scanners (IOSs) are utilized, offering an effective means of obtaining a direct digital representation of a patient's oral anatomy [3]. The iOS operating system captures and stores lighting projection data in a manner that is analogous to the way cameras do [2]. Consequently, the intraoral scanner is capable of quantifying the duration during which the subject surface reflects light [2]. Intraoral cameras utilize either video or static images for the purpose of scanning. Furthermore, it is possible to generate a three-dimensional image by merging many static photographs [2]. These fundamental elements serve as the foundation upon which each manufacturer constructs their respective procedures. The approaches employed for data collection in the context of intraoral cameras may exhibit variability [2].

Digital impression and scanning technology offer a range of advantages, including enhanced patient acceptance, minimized distortion of the impression material, and the potential for cost and time savings [4]. Furthermore, digital impressions offer chairside manufacture for CAD/CAM restorations, direct model viewing, and convenient impression repeatability [3]. The iOS platform also contributes to reducing patients' discomfort and anxiety levels. Contemporary patients who experience anxiety and a strong gag reflex frequently encounter difficulties tolerating traditional dental impressions. In such cases, the utilization of light-based techniques for tray and material manipulation presents a viable alternative [5]. Furthermore, the implementation of IOS technology has the potential to enhance the efficiency of clinical operations within the dental field, particularly in the context of complex impressions [5]. Moreover, this technology possesses the capacity to facilitate the permanent transfer and storage of digital images between the dental clinic and the laboratory [6].

A learning curve refers to a visual representation that illustrates the pace of learning over a period of time or in various contexts [7]. Several studies in the field of general medicine have investigated the effects of new technologies on the learning curves of system users [8-12]. Nevertheless, there is a scarcity of research conducted on the learning curve within the field of dentistry [13-16]. In addition, there is a lack of systematic or random clinical trials that have been undertaken to evaluate the learning curve associated with digital imprint techniques [17]. When considering the procurement of new equipment, it is imperative for a practicing dentist to have a comprehensive understanding of the learning curve associated with digital impressions and the suitability of the scanner [17].

Individuals utilizing digital intraoral scanners would require a significant amount of time and training in order to proficiently acquire the necessary skills to effectively and efficiently do restorations that exhibit both promptness and precision, ultimately resulting in optimal fit [18]. The decrease in the number of virtual model images and the reduction in the time allocated to capturing digital impressions can be attributed to the process of learning [17]. Enhancing the skill level of dentists in a specific technology or therapeutic treatment has the potential to decrease the duration of dental procedures while concurrently improving the standard of care delivered [19]. Furthermore, the accuracy of the scanned images produced by the single-image-based system was influenced by factors such as repeated experience, clinical experience, and the specific location being scanned. Consequently, it is imperative for users to have access to numerous practice opportunities in order to effectively use their clinical skills [19]. Recent advancements in dental technology have yielded newer models that exhibit enhanced accuracy and user-friendliness, hence facilitating their integration into clinical practice. However, it is important to acknowledge that not all dentists may readily adopt every emerging technology. The study conducted by Resende et al. (2019) determined that the accuracy of intraoral scans is influenced by factors such as operator skill, kind of intraoral scanner (IOS), and scan size. Due to the presence of highly competent operators and the utilization of smaller scan sizes, the accuracy of scans was consequently enhanced. Furthermore, it was seen that dentists with higher levels of expertise were able to perform scans at a faster rate [1].

In order to ensure the right fit of dental restorations and the precision of virtual articulation, it is imperative that dental models exhibit a high degree of accuracy [3]. The correctness of a dental impression procedure is influenced by the degree of trueness and precision [2]. The assessment of trueness and precision is based on the variability observed within a given test group, whereas the deviation of the tested impression method from the original geometry is indicative of trueness. In their systematic evaluation, Ahlholm et al. [2] determined that the precision of digital impressions is comparable to that of conventional impression techniques for the fabrication of crowns and short fixed partial dentures (FPDs). Both approaches are applicable in this context. In addition, it has been observed that digital imprint systems are capable of achieving a clinically acceptable fit for implant-supported crowns and fixed dental prostheses (FDPs). However, when it comes to large, full-arch FDPs, the traditional impression approach has been found to yield greater accuracy compared to the digital method [2]. Hence, the conventional approach may be deemed more favorable for obtaining a complete arch impression.

The topic of intraoral scanners has garnered significant attention from researchers due to its importance in clinical practice. Regrettably, there is a lack of research conducted in Saudi Arabia pertaining to improved oil recovery (IOR) techniques. In order to enhance comprehension of the current state of affairs, bridge the knowledge deficit in this significant domain, and establish a foundation for subsequent investigations, it is essential to embark upon a comprehensive examination of the utilization of intraoral scanners among the cohort of dental practitioners in Saudi Arabia. This will also aid scholars in assessing the current state of knowledge and improving future outcomes. Hence, the primary objective of this research was to examine the first-hand encounters of dental professionals in Saudi Arabia using intraoral scanners while also assessing their existing knowledge and subsequently enhancing their clinical practice based on the findings.

2. METHODS

A study was conducted to examine the characteristics and practices of dental practitioners in Saudi Arabia using a cross-sectional research design. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration after approval from the Ethical Committee of the University of Hail. The adherence to rigorous confidentiality protocols was observed with regard to the subject. Based on the sample size calculator provided by OpenEpi®, the study's projected sample size was determined to be 300, with a statistical power of 84% and a significance level (α) of 5%. This study incorporates dental professionals.

The study sample included 600 randomly selected practitioners from Saudi Arabia who were administered a self-explanatory questionnaire. After checking the literature, the questionnaires used in this study were designed. The validity of the questionnaire form was established during a pilot testing phase involving 40 dental practitioners. The questionnaire's relevance to the survey's topic was confirmed by college members from the Department of Restorative Dental Science at the College of Dentistry, University of Ha'il, Saudi Arabia, in collaboration with subject matter experts. Questionnaires were administered to practitioners to gather data based on their observations and experiences. Prior to the collection of data, participants provided their informed consent.

A total of 400 questionnaires were received, out of which 310 were deemed valid for inclusion in the study. The survey, along with a cover note underscoring the assurance of anonymous treatment of all responses, was distributed via email to the entire cohort of selected dental practitioners. The survey technology was utilized to automatically send four reminders at one-week intervals to individuals who did not respond initially. The distribution of surveys occurred throughout the months of July and September in the year 2021.

A pilot survey was conducted using a self-administered structured questionnaire consisting of 13 questions. The survey was administered to a convenient sample of 20 dental practitioners. Based on the comments received, it was determined that no modifications to the questionnaire were deemed necessary. Randomly, electronic surveys were distributed to dental practitioners in Saudi Arabia. The questionnaire was partitioned into the subsequent sections:

1. Practitioners’ demographic information such as gender, practice level, and practice experience.

2. Experience and benefits of intraoral scanners.

3. Require skills and training of IOS.

4. Knowledge of IOS usage.

The study included various statistical analyses, including frequencies, crosstabs, chi-square, and Fisher's exact tests, to assess the statistical significance of gender, practice level, and experience disparities in the understanding of intraoral scanners among dental practitioners in Saudi Arabia. The surveys that had been filled out were inputted into Windows Excel and subjected to statistical analysis using the Social Sciences software version 28 (IBM SPS Statistics). The data that was obtained was subjected to analysis utilizing descriptive statistics, specifically employing numerical values and percentages.

3. RESULTS

A survey was conducted, and a total of 310 dentists participated by completing the questionnaire. Among the participants, there was a total of 161 women, accounting for 51.8% of the sample, while 149 men were also included, representing 47.9% of the total population. The majority of individuals, specifically 198 or 63.7%, were general practitioners. Specialists (restorative dentists) accounted for the second largest group, with 80 subjects, equivalent to 25.7%. Consultants represented the smallest group, including 32 subjects or 10.3%.

Table 1 displays the distribution of questions and corresponding scores pertaining to knowledge of the IOS operating system. The influence of gender, experience, and practice level on knowledge of IOS is demonstrated in Tables 2-4. A total of 310 dentists were surveyed, of which 180 (58.1%) were found to be unfamiliar with IOS, while the remaining 130 (41.9%) were knowledgeable about it. There is no significant difference in the perceptions of IOS between men and women, as indicated by the statistical analysis (p > 0.05), as presented in Table 2. The data presented in Table 4 indicates that consultants and specialists in restorative dentistry possessed notably greater levels of knowledge compared to general practitioners, with statistical significance at a p-value of less than 0.01. Furthermore, the findings presented in Table 3 indicate that dentists who possess over a decade of experience and those with a professional tenure ranging from five to ten years exhibit a higher level of comprehension of IOS compared to their counterparts with less than five years of experience (p<0.01).

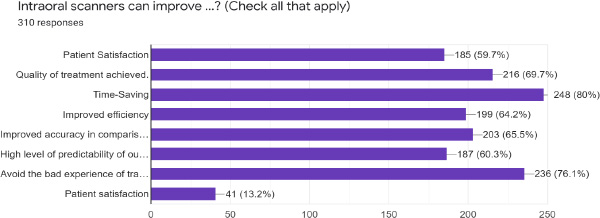

When considering the utilization of IOS in dental practice, a majority of participants (70.6%) do not employ this technology, while less than one-third of participants do. The findings shown in Tables 3 and 4 indicate that the utilization of IOS in dental clinics exhibits notable variations depending on the level of experience and practice (p>0.01). However, there is no significant disparity observed in terms of gender (p>0.05). Moreover, a large proportion of the participants (52.3%) expressed their intention to acquire IOS, with notable discrepancies observed across gender, experience, and degree of practice (p<0.05). Fig. (1) illustrates the enhancement of clinical practice through the utilization of intraoral scanners.

In contrast to conventional methods, a majority of participants hold the belief that IOS will ultimately supplant them, enhance their quality, and provide superior visual appeal. Based on the analysis of dentists' gender, experience, and practice level, no statistically significant associations were found between the perception of intraoral scanning (IOS) as a replacement for traditional treatments, its potential to enhance quality, and its ability to improve aesthetics (p>0.05).

| Variable | - | Response n (%) |

| Tried intra-oral scanner | Yes | 130 (41.9) |

| No | 180 (58.1) | |

| Use of IOS in dental office | Yes | 91 (29.4) |

| No | 219 (70.6) | |

| Plan to purchase IOS | Yes | 162 (52.3) |

| Already have | 56 (18.1) | |

| No | 92 (29.7) | |

| IOS can Improve | Patient satisfaction | 7 (2.3) |

| Quality of treatment | 5 (1.6) | |

| Time | 13 (4.2) | |

| Treatment efficiency | 4 (1.3) | |

| Accuracy | 2 (0.6) | |

| Predictability of outcome | 2 (0.6) | |

| Avoid bad experience of traditional impressions | 5 (1.6) | |

| More than one answer | 272 (87.7) | |

| IOS improve quality compared to traditional | Yes | 257 (82.9) |

| No | 53 (17.1) | |

| Replace traditional | Yes | 190 (61.3) |

| No | 120 (38.7) | |

| More aesthetic | Yes | 258 (83.2) |

| No | 52 (16.8) | |

| Require skills and training | Yes | 184 (59.4) |

| No | 126 (40.6) | |

| IOSs have the same accuracy as conventional for 3units FPDs | Yes | 170 (54.8) |

| No | 140 (45.2) | |

| IOSs have the same accuracy as the conventional in the implant | Yes | 183 (58.8) |

| No | 127 (40.8) | |

| IOSs have the same accuracy as conventional in CD | Yes | 183 (58.8) |

| No | 127 (40.8) |

| Variable | - | Gender | p-value | |

| Male | Female | |||

| Tried intra-oral scanners | Yes | 60 (40.3) | 70 (43.5) | 0.078 |

| No | 89 (59.7) | 91 (56.5) | ||

| Use of IOS in dental office | Yes | 46 (30.9) | 45 (28.0) | 0.085 |

| No | 103 (69.1) | 116 (72.0) | ||

| Plan to purchase IOS | Yes | 86 (57.7) | 76 (47.2) | 0.007 |

| Already have | 26 (17.4) | 30 (18.6) | ||

| No | 37 (24.8) | 55 (34.2) | ||

| IOS can improve | Patient satisfaction | 3 (2.0) | 4 (2.5) | 0.023 |

| Quality of treatment | 1 (0.7) | 4 (2.5) | ||

| Time | 7 (4.7) | 6 (3.7) | ||

| Treatment efficiency | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Accuracy | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Predictability of outcome | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Avoid bad experience of traditional | 3 (2.0) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| More than one answer | 132 (88.6) | 140 (87.0) | ||

| IOS improve quality compared to traditional | Yes | 124 (83.2) | 133 (82.6) | 0.119 |

| No | 25 (16.8) | 28 (17.4) | ||

| Replace traditional | Yes | 95 (63.8) | 95 (59.0) | 0.064 |

| No | 54 (36.2) | 66 (41.0) | ||

| More aesthetic | Yes | 121 (81.2) | 137 (85.1) | 0.080 |

| No | 28 (18.8) | 24 (14.9) | ||

| Require skills and training | Yes | 92 (61.7) | 92 (57.1) | 0.066 |

| No | 57 (38.3) | 69 (42.9) | ||

| IOSs have the same accuracy as conventional for 3units FPDs | Yes | 85 (57.0) | 85 (52.8) | 0.069 |

| No | 64 (43.0) | 76 (47.2) | ||

| IOSs have the same accuracy as the conventional in the implant | Yes | 85 (57.0) | 98 (60.9) | 0.073 |

| No | 64 (43.0) | 63 (39.1) | ||

| IOSs have the same accuracy as conventional in CD | Yes | 92 (61.7) | 91 (56.5) | 0.060 |

| No | 57 (38.3) | 70 (43.5) | ||

| Variable | - | Experience Level | p-value | ||

| < 5 yrs. | 5-10 yrs. | > 10 yrs. | |||

| Tried intra-oral scanner | Yes | 59 (31.1) | 48 (58.5) | 23 (60.5) | 0.00 |

| No | 131 (68.9) | 34 (41.5) | 15 (39.5) | ||

| Use of IOS in dental office | Yes | 37 (19.5) | 34 (41.5) | 20 (52.6) | 0.00 |

| No | 153 (80.5) | 48 (85.5) | 18 (47.4) | ||

| Plan to purchase IOS | Yes | 105 (55.3) | 38 (46.3) | 19 (50) | 0.024 |

| Already have | 18 (9.5) | 24 (29.3) | 14 (36.8) | ||

| No | 67 (35.3) | 20 (24.4) | 5 (13.2) | ||

| IOS can improve | Patient satisfaction | 4 (2.1) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (2.6) | 0.016 |

| Quality of treatment | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Time | 9 (4.7) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (5.3) | ||

| Treatment efficiency | 3 (1.6) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Accuracy | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Predictability of outcome | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Avoid bad experience of traditional | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| More than one answer | 169 (88.9) | 71 (86.6) | 32 (84.2) | ||

| IOS improve quality compared to traditional | Yes | 160 (84.2) | 65 (79.3) | 32 (84.2) | 0.076 |

| No | 30 (15.8) | 17 (20.7) | 6 (15.8) | ||

| Replace traditional | Yes | 117 (61.6) | 46 (56.1) | 27 (71.1) | 0.058 |

| No | 73 (38.4) | 36 (43.9) | 11 (28.9) | ||

| More aesthetic | Yes | 159 (83.7) | 69 (84.1) | 30 (78.9) | 0.072 |

| No | 31 (16.3) | 13 (15.9) | 8 (21.1) | ||

| Require skills and training | Yes | 124 (65.3) | 44 (53.7) | 16 (42.1) | 0.001 |

| No | 66 (34.7) | 38 (46.3) | 22 (57.9) | ||

| IOSs have the same accuracy as conventional for 3units FPDs | Yes | 108 (56.8) | 46 (56.1) | 16 (42.1) | 0.024 |

| No | 82 (43.2) | 36 (43.9) | 22 (57.9) | ||

| IOSs have the same accuracy as the conventional in the implant | Yes | 115 (60.5) | 50 (61) | 18 (47.4) | 0.032 |

| No | 75 (39.5) | 32 (39) | 20 (52.6) | ||

| IOSs have the same accuracy as conventional in CD | Yes | 113 (59.5) | 49 (59.8) | 21 (55.3) | 0.061 |

| No | 77 (40.5) | 33 (40.2) | 17 (44.7) | ||

The majority of dental professionals hold the belief that the utilization of intraoral scanners (IOS) necessitates certain expertise and instruction. Regarding the aspect of training, the analysis revealed no statistically significant disparities between dentists of different genders or practice levels (p>0.05). However, notable distinctions were observed based on experience (p<0.01), as indicated in Tables 2-4.

A majority of dentists hold the belief that intraoral scanners (IOSs) exhibit comparable levels of accuracy to conventional methods when fabricating three-unit fixed partial dentures (FPDs), implant prostheses, and complete dentures. The statistical analysis revealed that the expertise of dentists had a significant impact on the utilization of intraoral scanners (IOSs) to produce three-unit fixed partial dentures (FPDs) (p<0.05). However, no significant associations were found between gender and practice level and the use of IOSs for FPD manufacturing (p>0.05). Significant differences were seen in the utilization of IOSs for implant prosthesis based on experience and practice level (p<0.05), however, no significant differences were found based on gender (p>0.05). In addition, there is considerable variation in the amount of training when it comes to utilizing IOSs for

| Variable | - | Practice Level | p-value | ||

| GP | Specialist | Consultant | |||

| Tried intra-oral scanner | Yes | 66 (33.3) | 45 (56.3) | 19 (59.4) | 0.00 |

| No | 132 (66.7) | 35 (43.8) | 13 (40.6) | ||

| Use of IOS in dental office | Yes | 43 (21.7) | 31 (38.8) | 17 (53.1) | 0.00 |

| No | 155 (78.3) | 49 (61.3) | 15 (46.9) | ||

| Plan to purchase IOS | Yes | 108 (54.5) | 40 (50) | 14 (43.8) | 0.035 |

| Already have | 24 (12.1) | 19 (23.8) | 13 (40.6) | ||

| No | 66 (33.3) | 21 (26.3) | 5 (15.6) | ||

| IOS can improve | Patient satisfaction | 5 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.017 |

| Quality of treatment | 3 (1.5) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (3.1) | ||

| Time | 10 (5.1) | 3 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Treatment efficiency | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.1) | ||

| Accuracy | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (3.1) | ||

| Predictability of outcome | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Avoid bad experience of traditional | 3 (1.5) | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| More than one answer | 173 (87.4) | 70 (87.5) | 29 (90.6) | ||

| IOS improve quality compared to traditional | Yes | 164 (82.8) | 66 (82.5) | 27 (84.4) | 0.088 |

| No | 34 (17.2) | 14 (17.5) | 5 (15.6) | ||

| Replace traditional | Yes | 118 (59.6) | 51 (63.7) | 21 (65.6) | 0.05 |

| No | 80 (40.4) | 29 (36.3) | 11 (34.4) | ||

| More aesthetic | Yes | 168 (84.8) | 62 (77.5) | 28 (87.5) | 0.08 |

| No | 30 (15.2) | 18 (22.5) | 4 (12.5) | ||

| Require skills and training | Yes | 122 (61.6) | 49 (61.3) | 13 (40.6) | 0.14 |

| No | 76 (38.4) | 31 (38.8) | 19 (59.4) | ||

| IOSs have the same accuracy as conventional for 3units FPDs | Yes | 107 (54) | 49 (61.3) | 14 (43.8) | 0.064 |

| No | 91 (46) | 31 (38.8) | 18 (56.3) | ||

| IOSs have the same accuracy as the conventional in the implant | Yes | 123 (62.1) | 47 (58.8) | 13 (40.6) | 0.008 |

| No | 75 (37.9) | 33 (41.3) | 19 (59.4) | ||

| IOSs have the same accuracy as conventional in CD | Yes | 122 (61.6) | 45 (56.3) | 16 (50) | 0.027 |

| No | 76 (38.4) | 35 (43.8) | 16 (50) | ||

Shows how intraoral scanners improves clinical practice.

the fabrication of complete dentures. However, there is no statistically significant correlation between the gender and experience of dentists in this context, as indicated by a p-value greater than 0.05.

4. DISCUSSION

Digital dental technology has become an indispensable component of contemporary clinical practice. Dental students are currently being raised in an era characterized by perasive digital technology, which significantly shapes their inclinations, anticipations, and methods of receiving novel information. There is a growing interest among dentists to integrate digital technologies into their educational practices. In addition, the expeditious advancement of digital technology presents a formidable obstacle for educators, demanding continual adaptations and modifications to the educational syllabus. Dental professionals encounter a wide array of digital technologies. The primary objective of this study revolved around examining the acceptance and rejection experienced by the individuals under investigation. The study placed particular emphasis on identifying the obstacles and driving forces encountered throughout their journey [20]. The scope of these capabilities surpasses the technological limitations of digital dental technologies. The adoption of dental technologies exhibits variability based on individual preferences and the specific technology in question. However, it is possible to discern overarching patterns that need additional exploration in future scholarly investigations. The utilization of intraoral scanners is experiencing significant growth, leading to their widespread adoption in clinics across the globe. Consequently, the primary objective of this research endeavor was to ascertain the level of knowledge and attitudes exhibited by dentists in Saudi Arabia with regard to intraoral scanners.

There has been a notable surge in research activity surrounding intraoral scanners, indicating a growing interest in this field. Numerous scholars have chosen to prioritize the precision and temporal efficacy of intraoral scanners alongside the viewpoints of patients, dentists, students, and helpers [21-23].

In the current investigation, a notable proportion of dental professionals (29.4%) reported the utilization of intraoral scanners within their clinical settings. The adoption of intraoral scanners by users is mostly influenced by their experience with the scanner [24, 25]. A significant number of dental practitioners exhibit reluctance in adopting these novel instruments owing to the considerable amount of time required to acquire proficiency in their use. According to the authors, there is a belief that the acquisition of intraoral scanning skills poses a comparable level of difficulty for both dental students and recently graduated dentists, as compared to the conventional practice of obtaining traditional impressions [18]. The examination of the utilization of intraoral scanners is an essential undertaking in the process of incorporating them into routine clinical procedures.

The survey results indicate that dentists who participated in the study generally expressed satisfaction and a positive attitude towards the utilization and effectiveness of intraoral scanners in their clinical practice. The concept of efficiency was operationalized by Lee et al. [21] as the measurement of time and the frequency of retakes or rescans. In addition to several clinical advantages, it has been observed that Intraoral Scanning (IOS) exhibits more efficiency compared to traditional impression creation methods. This is primarily attributed to the elimination of tasks such as mixing and setting impression material, sanitizing the impression, and creating stone models [26, 27]. Undesirable areas can be readily eliminated to facilitate recapture or subsequent rescanning [28].

Conversely, the presence of significant faults in the impressions, such as the presence of bubbles along the preparation boundaries or unclear margins, will result in the complete invalidation of the imprint. Consequently, the entire impression will necessitate being remade [29]. The development of IOS and the process of impression formation are likely to require different sets of skills [17, 21, 23]. The investigation involved the exposure of dentists to several intraoral scanners. It was observed that variations in the success of impression production may occur due to changes in the system and scanning procedures.

The implementation of IOS in dental clinics necessitates consideration of a learning curve [29-31]. Individuals with a keen interest in technology and computers, such as young dentists, will discover a seamless integration of IOS into their professional endeavors. According to the findings of the present study, a majority of the dentists who participated in the survey expressed the view that the utilization of intraoral scanners (IOS) necessitates a certain level of proficiency and specialized training. Intraoral scanners, similar to other imprint techniques, have a learning curve [17]. Certain regions within the oral cavity, such as the distal surfaces of the final tooth in a dental arch and the proximal surfaces adjacent to a confined saddle, may present difficulties when attempting to obtain accurate digital impressions with intraoral scanners.

Novice individuals may encounter challenges while attempting to use the tip of intraoral scanners, as they navigate the device in accordance with the scanner's indications, which are derived from previously recorded surfaces [30]. It is probable that the utilization of IOS and the act of producing impressions require different sets of skills [23, 32]. The study involved the exposure of dentists to several intraoral scanners. It was observed that variations in the success of impression formation may occur due to variances in the system and scanning methods [32].

The assessment of impression quality can be performed in real-time by the physician and dental technician via IOS technology [33]. Upon completion of the scan, the dentist has the capability to promptly transmit it to the laboratory via email. Subsequently, the technician possesses the ability to meticulously examine the scan with precision [33. 34]. Assuming that the dental technician expresses dissatisfaction with the quality of the optical impression received. In such circumstances, patients have the option to promptly request the clinician to create a replacement, thereby avoiding unnecessary delays or the need for a subsequent session. This particular characteristic enhances and reinforces the exchange of information between the dentist and dental technician [33, 34].

Based on the findings of this study, a considerable proportion of the participating dental professionals expressed the belief that Intraoral Scanning (IOS) has the potential to supplant the conventional approach. The scientific literature acknowledges optical impressions as clinically good and comparable to conventional impressions for single tooth restoration and fixed partial prostheses consisting of 4-5 pieces [23]. Indeed, optical impressions have been found to yield comparable levels of trueness and precision to traditional impressions for short-span restorations [35, 36]. Nevertheless, when it comes to extensive restorations like partial fixed prostheses with over five parts or full-arch prostheses on natural teeth or implants, it seems that optical impressions are not as precise as conventional impressions. The discrepancy observed in the inaccuracy produced during the process of capturing the complete dental arch using intraoral scanning technology seems to be incongruent with the feasibility of creating long-span restorations. Consequently, traditional impressions continue to be necessary for the fabrication of such restorations [35, 36].

The present investigation possesses several limitations as it just adopts a cross-sectional design. To obtain more precise results regarding the accuracy and practical applications of intraoral scanning (IOS) in the fields of restorative dentistry, as well as orthodontics, it is imperative to conduct further clinical investigations. There is a need for additional some objective index and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) focusing on interventions for iOS in order to conduct a comprehensive systematic review of the existing literature. This review should be based on a sufficient number of instances or patients who have been adequately treated. The inclusion of a clinical scenario could offer supplementary insights about the challenges and complexities associated with impression making at the early stages of clinical practice, necessitating careful consideration of the absence of practical experience with real patients. The implications of this study suggest that dentists with greater clinical experience may exhibit increased proficiency in impression production, leading to a larger likelihood of favoring this method over intraoral scanning (IOS). Further investigation is warranted to explore the preferences and attitudes of dentists regarding intraoral scanning (IOS) and traditional impression making techniques.

CONCLUSION

Based on the limitations of this research, it can be concluded that dentists exhibit a notable level of satisfaction and hold a favorable disposition towards the implementation of intraoral scanning (IOS) technology within the context of clinical dentistry practice. Despite the potential advantages of intraoral scanning, a significant number of dentists continue to prefer conventional impression-taking due to its expedited process. There is a need for increased availability of IOS courses within the framework of continuing education programs for dental practitioners. In order to effectively address a range of clinical settings, it is imperative for dental schools to provide their students with proficiency in both methodologies.

The utilization of digital devices and applications is becoming more prevalent in the context of fundamental dental care. Hence, it is imperative to acknowledge the inclination towards digitization and the ongoing modifications in the dentistry curriculum as essential factors in preparing prospective dentists for their professional endeavors. The establishment of universally acknowledged digital education standards is crucial, particularly among dentistry colleges within specific nations.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

I.K.A. and A.A.M.: Contributed to the concept of the research, study design, statistical analysis, writing the original draft, and reading and editing the final paper; A.H.A. and A.S.A.: Contributed to data gathering and statistical analysis. The final manuscript was reviewed and approved by all writers.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| CAD/CAM | = Computer-aided Design And Computer-aided Manufacturing |

| IOS | = Intraoral Scanner |

| IOSs | = Intraoral Scanners |

| FPDs | = Fixed Partial Dentures |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The Ethics Committee of Scientific Research, University of Hail, Saudi Arabia, approved the protocol of this study. (Ethical number: H-2021-148).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data that support the results of this study are accessible from the corresponding author [I.A.I] upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.